Home and Hearth

Wood elves make their homes in graceful pavilions under the stars in forest clearings, rarely remaining in the same place for more than a day or two. Shield dwarves carve workshops and mines from the hearts of mountains, fortifying their homes. Goblins and ores favor warrens of burrows in the wilderness. Human homes run the gamut from a herder's yurt in the Endless Waste to a prince's palatial townhouse along Waterdeep's richest street. Any experienced traveler soon comes to appreciate that there are as many different ways of life in Faerûn as there are kinds of people.

Orc-infested mountain ranges, troll-haunted wastelands, wild woods guarded by secretive and unfriendly fey creatures, and sheer distance divide Faerûn's nations from each other. Faerûn's city-states and kingdoms are small islands of civilization in a vast, hostile world, held together by tenuous lines of contact.

Government

The most common forms of government in the Heartlands are feudal monarchies, generally found in the larger realms and more isolated lands, and plutocratic monarchies, common among city-states and realms dominated by trade. In either case, a hereditary lord, king, monarch, or potentate holds the power to make laws, dispense justice, and manage foreign affairs. The monarch's power is checked to a greater or lesser degree by the powerful feudal lords or wealthy merchant princes who owe him allegiance.

Since the nobles or great merchants are ruled only by their own consent, many Heartlands city-states and kingdoms are realms of weak central authority, and strongly independent nobility. A monarch who pushes a willful noble too far might drive that noble to open revolt - and in many cases the noble's strength-of-war is nearly the match of the overlord's, so quelling a rebellious province is hardly an easy undertaking. Worse yet, a monarch may be forced to solicit the support (or at least neutrality) of other nobles of the realm as he goes about suppressing one of their peers. This support usually comes at a price, further eroding royal authority.

Strong thrones may be rare, but they do exist. The Cormyr of King Azoun Obarskyr was a shining example of the good that can come of a strong monarchy in the hands of a wise and courageous leader. Unfortunately, the death of Azoun and the plague of evils that descended on that land have left Cormyr's fate uncertain. Azoun's daughter, the Regent Alusair, must chart a careful course among the realm's nobility as she attempts to retain the power her father held.

Civil warfare in the mercantile city-states of the Inner Sea is rare, but the lords and princes who rule these small realms must contend with merchant-nobles every bit as willful and haughty as a feudal lord in his castle. In the walls of a city-state, a wealthy noble thinks carefully before defying the ruler, since he lacks the safety of miles of roads and empty lands between his demesne and his ruler's army. But it also means that any noble's own private army is only an hour's march from the seat of power. Powerful lords deal with overmasters they don't like through palace coups, feuds, and assassinations.

City and Countryside

In the Heartlands, a very basic division separates people into two distinct groups: townsfolk and rural folk. The dividing line is blurry at times - a large village or small town blends many of the characteristics of rural and urban life. The division is not exclusive. Even in Faerûn's largest cities, farmers and herders till crops and tend livestock within the shadow of the city walls.

In most lands, nine people live in the countryside for every city-dweller. Large cities are hard to sustain, and in Faerûn's Heartlands, most people are compelled to work the land in order to feed themselves. Large towns and cities can only flourish in places that enjoy easy access to farmlands and resources producing a surplus of food.

Rural Life

In painting a picture of the average Faerûnian, an observer discovers that the most ordinary, unremarkable, and widespread representative of Faerûn's incredible diversity is a simple human farmer. She lives in a small house of wood, sod, or thatch-roofed fieldstone, and she raises staple crops such as wheat, barley, corn, or potatoes on a few dozen acres of her own land.

In some lands the common farmer is a peasant or a serf, denied the protection of law and considered the property of whichever lord holds the land she lives on. In a few harsh lands, she is a slave whose backbreaking work is rewarded only by the threat of the lash and swift death should she ever defend herself from the overseers and lords who live off her endless toil. But in the Heartlands she is free if somewhat poor, protected from, rapacious local lords by the law of the land, and allowed to choose whatever trade or vocation she has a talent for in order to feed her family and raise her children.

The common farmer's home is within a mile or so of a small village, where she can trade grain, vegetables, fruit, meat, milk, and eggs for locally manufactured items such as spun cloth, tools, and worked leather. Some years are lean, but Faerûn's Heartlands are rich and pleasant, rarely knowing famine or drought.

A local lord guards the common farmer from bandits, brigands, and monsters. He is a minor noble whose keep or fortified manor house watches over her home village. The noble appoints a village constable to keep order and might house a few of the king's soldiers or his own guards to defend against unexpected attack. Within a day's ride, a more powerful noble whose lands include one or two dozen villages like the typical commoner's has a castle manned by several dozen soldiers. In dangerous areas, defenses are much sturdier and trained warriors more numerous.

City Life

Typical townsfolk or city-dwellers are skilled crafters of some kind. Large cities are home to numbers of unskilled laborers and small merchants or storeowners, but the most city-dwellers work with their hands to make finished goods from raw materials. Smiths, leatherworkers, potters, brewers, weavers, woodcarvers, and all other kinds of artisans and tradesfolk working in their homes make up the industry of Faerûn.

The city-dweller lives in a wood or stone house, shingled with wooden shakes or slate, that sits shoulder-to-shoulder with its neighbors in great sprawling blocks through which myriad narrow streets and alleyways ramble. In small or prosperous towns, his home might include a small plot of land suitable for a garden. Many relations, boarders, or whole families of strangers share his crowded home. If he isn't married, he might live as a boarder with someone else.

In some cities he may be required to join great guilds of craftsfolk with similar skills, or risk imprisonment. In others, agents of the city's ruling power closely monitor his activities and movements, rigidly enforcing exacting laws of conduct and travel. But in most cases, he is free to pack up and leave or change trades whenever he likes.

He purchases food from the city's markets, which sometimes means that he is stuck with whatever fits within his budget. A prosperous man can work hard and comfortably feed his family, but in lean times the poorer laborers must make do with stale bread and thin soup for weeks on end. Every city depends on a ring of outlying villages and farmlands to supply it with food on a daily basis. Most also possess great granaries against times of need, and many provisioners and grocers specialize in stocking nonperishable foodstuffs at times of the year when fresh food is not available in the city's markets.

A city of any size is probably protected by a city wall, patrolled by the city watch, and garrisoned by a small army of the soldiers of the land. Rampaging monsters or bloodthirsty bandits don't trouble the average city-dweller, but he rubs elbows every day with rogues, thieves, and cutthroats. Even the most thoroughly policed cities have neighborhoods where anybody with a whit of common sense doesn't set foot.

Wealth And Privilege

Just as nine out of ten Faerûnians live in small villages and freeholds in the countryside, roughly nineteen out of twenty people are of common birth and ordinary means. They rarely accumulate any great amount of wealth - a prosperous innkeeper or skilled artisan might be able to set her hands on a few hundred gold pieces, but most common farmers and tradesfolk are lucky if they have more than forty or fifty silvers to their name.

In many lands, common-born people are bound by law to defer to their betters, the lords and ladies of the nobility. Even if the law does not require deference, it's usually a good idea. Nobles enjoy many protections under the law and in some cases can escape punishment for assault, provocation, or the outright murder of a commoner.

The typical noble is a rural baronet or lordling whose lands span only a few miles, ruling over a few hundred common folk in the king's name. She collects taxes from the villagers and farmers and is vastly more wealthy than all but the most prosperous entrepreneurs in her lands. With her wealth and power come certain responsibilities, of course. She is answerable to her own feudal masters for the lawkeeping and good order of her lands. She can be called upon to provide soldiers and arms for her lords' causes. And, most important, most nobles feel some obligation to protect the people in their charge against the depredations of monsters and banditry. To this end, most nobles frequently deal with companies of adventurers, retaining their services to clear out troublesome monsters and hunt down desperate outlaws.

Class and Station

As Cormyr's recent troubles prove, the Heartlands of Faerûn are not always stable or safe. Incursions of monstrous hordes of orcs, ogres, or giants can easily overrun even stoutly defended cities. Would-be kings continually challenge the powers of the land from within, seeking to unseat the ruler. Proud and arrogant foreign powers watch warily for any sign of weakness, always ready to annex a province or sack a city. Magical disasters, plagues, and flights of raging dragons can lay low even the most peaceful and secure lands.

To fend off these dangers, most realms of the Heartlands have developed an enlightened feudal system over centuries of strife and warfare. Lords hold lands in the name of their king, raising armies and collecting taxes to defend the realm. They are expected to answer their king's call to arms and to defend his interests to the best of their ability. This reasonably effective system supports independent warbands in the defense of far-flung territories.

The Peasantry

As previously noted, common farmers and simple laborers make up most of the human population of Faerûn's kingdoms and cities. The lowest class across all of the Heartlands, the peasantry forms the solid base upon which the power structures of nobles, merchants, temples, and kingdoms all rest.

Most Heartlands peasants are not bound to the lands they work and owe no special allegiance to the lord who rules over them, other than obeying his laws and paying his taxes. They do not own their farmlands but instead rent croplands and pastures from the local lord, another form of taxation normally accounted at harvest time.

In frontier regions such as the Western Heartlands, many common farmers own and work their own lands. These people are sometimes known as freeholders if no lord claims their lands, or yeomen if they are common landowners subject to a lord's authority.

Tradesfolk and Merchants

A step above the common peasantry, skilled craftsfolk and merchants generate wealth and prosperity for any city or town. The so-called middle class is weak and disorganized in most feudal states, but in the great trade cities of the Inner Sea, strong guilds of traders and companies of craftsfolk are strong enough to defy any lord and protect themselves from the monarch's authority by the power of their coffers.

The wealthiest merchants are virtually indistinguishable from mighty lords. Even if born from peasant stock, a merchant whose enterprises span. a kingdom might style himself "lord" and get away with it.

Clergy

Existing alongside the feudal relationship of a rural province or guild organization of a trading city, the powerful temples of Faerûn's deities parallel the king's authority. The lowest-ranking acolytes and mendicants are rarely reckoned beneath the station of a well-off merchant, and any cleric or priest in charge of a temple holds power comparable to that of a baronet or lord. The high priests of a faith favored in a particular land are equal to the highest nobility.

Many of Faerûn's temples are implacable enemies or bitter rivals. In most rural regions, folk tend to follow one or two deities who are particularly active or actively supported in their immediate locale. If a powerful and benevolent temple of Tempus happens to stand just outside a small town, many townspeople will worship Tempus, even if farmers are generally more inclined to the teachings of Chauntea and merchants might otherwise follow Waukeen.

Low Nobility

Descended. from warriors who won land to rule (or valuable hereditary positions with handsome stipends) in service to their homeland or king, the low nobility is the backbone of the feudal realm. From their sons and daughters are drawn the knights and officers of the king's armies, and from their house guards and vaults come the manpower and gold necessary to field the kingdom's fighting power. They administer the king's justice within their demesnes and collect his taxes.

Low nobles hold court to settle disputes that occur on their land or under their responsibility, and are expected to try cases of low justice - just about any crime short of murder or treason. They claim a tithe of any wealth in food or gold generated by the commoners who work their land, and may levy local taxes as long as they do not interfere with the monarch's taxes. In return, they are expected to see to the defense and prosperity of their fiefs. Regrettably, more than one local lord is nothing more than a thief in a castle, wringing every copper he can from the people he rules.

A new breed of low noble is rising in prosperous lands such as Sembia and Impiltur - the so-called merchant prince. A merchant establishes an enterprise or industry of great and lasting value, and then passes it to his heirs. Over time these upstarts may hope to purchase with gold the noble title otherwise won only by valor in days long past.

Knights, lords, baronets, and barons are accounted low-landed nobles. Lord-mayors, sheriffs, commanders, wardens, and seneschals are low nobles who hold titles but no lands.

High Nobility

Frequently related by blood or marriage to the ruling family, high nobles are those who are due allegiance from some number of low nobles. Unlike low nobles, who frequently carry noble titles without lands, high nobles are usually landed, commanding great fiefs that could be considered small kingdoms in their own right.

High nobles hear disputes that lower nobles cannot settle, and dispense justice for all but the most heinous of crimes. Like low nobles, they collect taxes in the ruler's name and levy additional taxes as they see fit. They maintain personal armies sometimes numbering in the hundreds and use them to vigorously police and patrol their lands.

The high counselors of a kingdom or realm are often accounted high nobles, even if they are not rewarded with lands. The stipends and royalties associated with their titles make them some of the wealthiest people in a kingdom.

Counts, viscounts, dukes, earls, and marquises are high-landed nobles. Lord-governors and high counselors are high-titled nobles. Grand dukes, archdukes, and. princes are considered royalty, even if they are not immediately related to the ruling house.

Titles and Forms of Address

Most realms across Faerûn have some form of nobility, and many also have ruling royalty. All have officials who sport titles, from a simple "Master of the . . ." to such mouthfuls as "His Most Exalted and Terrible, Beloved of the Gods and Venerable Before All His People, Hereditary and-may-his-line-prosper-forever. . . " Many long and involved tomes at Candlekeep outline the intricacies of the various systems of titles, their ranks and precedence. Here's a brief overview. -

| Position | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| Commoner | Goodman | Goodwife or Maid |

| Knight, Officer | Sir | Lady, or Lady Sir |

| Mayor. Warden, Commander, Seneschal | Lord | Lady or Lady Lord |

| Baron, Count | Milord | Milady |

| Duke, Viscount, Marquis | High Lord | High Lady |

| Grand Duke, Prince, | Highness | Highness |

| King, Queen, Archduke | Majesty | Majesty |

General titles for nobility of uncertain rank include "Zor/Zora" in Mulmaster, "Syl" in Calimshan, and "Saer" (for both genders) almost everywhere else. This latter term also applies to children of nobility too young or low-ranking to have been awarded titles of their own.

In general Heartlands usage, if the head of a noble house is "Lord Grayhill," his children are all "Saer [name] Grayhill." His widowed or aged parents, or older uncles and aunts living but bypassed in precedence are "Old Lord (or Lady) Grayhill."

Various Faerûnian professions and races have popular verbal greetings and farewells, but "Well met" for both is almost universal. Oloré ("oh-LOR-ay") serves the same purpose around the Sea of Fallen Stars, and human nobles are adopting the elven "Sweet water and light laughter until next we meet." Merchants of all races often use the terse dwarven "I go."

Families

As a rule, adventurers do dot choose to begin families while they actively pursue their careers - lich lords and raging dragons tend to make a lot of widows and orphans. But for the common folk of the land and even the great lords, the most important thing in the world is their family. Parents carefully train their children in the trades they follow and secure their property for the day they pass their hopes and businesses to their children.

The Heartlands of Faerûn are generally enlightened and liberal regarding gender roles. Women are as free as men to own property, run businesses, and run off to become adventurers. Many of Faerûn's most powerful heroes are women. Some societies observe strict codes of gender conduct (some matriarchal, not patriarchal), but this is not the case in most of Faerûn.

Marriage

In almost every society, human and nonhuman, marriage ceremonies are celebrated with feasting, dancing, song, and, stories. The exact customs vary wildly from land to land, but in any Heartlands village a marriage is an excuse to set aside work for a day and celebrate.

Among nobles, arranged marriages are not unusual, but very few commoners marry against their will. Marriages for love are far more common. Divorce is rare, particularly since standards of marital fidelity are decidedly relaxed in some lands. It's not unknown for a man or woman to have more than one spouse at the same time, but such arrangements are rare and usually reserved for those who have enough money or power to do whatever they like.

Children

Children are regarded as a blessing and a treasure throughout the Heartlands. Large families are quite common, especially in relatively safe and prospectus regions. The careful attention of clerics, healers, and divine healing magic makes childbirth reasonably safe in most civilized lands.

In parts of Faerûn, particularly in rural areas dependent on agriculture, responsibilities and tasks come to children early. Children from urban areas begin to learn their parents' trades at a similarly early age. By eight to ten years of age, most children are well on their way to acquiring the knowledge necessary to continue in their parents' work. The children of nobles and wealthy merchants are formally schooled and enjoy significantly more leisure time until their mid-teens.

Ironically, children from nomadic and "savage" groups may enjoy the happiest childhood, since they're encouraged to develop the skills that will serve them as adults by playing in the wilds. This is not to say that children are allowed to roam free without supervision from discreet guards - life in Faerûn is too dangerous to allow innocents to wander completely unguarded.

Old Age

Common laborers, farmers, and peasants work until the day they die, unless they have strong and dependable children who can take over the family enterprise and care for them. A life without work is usually only an option for the wealthy, including the few adventurers who live to middle age to enjoy their loot in peace. On the bright side, the blessings of the gods and the beneficial prayers and spells of clerics and healers avert many of the worst ravages of old age. Elderly folk rarely suffer extended infirmities or disabling illness until just before death.

Learning

Formal schooling is the exception rather than the rule in the Heartlands. Only the children of wealthy or highborn parents receive any real education. Even so, most Faerûnians of civilized lands are literate and understand the value and the potential power of the written word.

Most people learn to read and write from their parents or from clerics of Oghma or Deneir. Very few schools exist. Those that do are expensive, exclusive, private schools or academies that spend as much time teaching riding, courtly manners, and swordplay as they do on true academic matters. Most young nobles or merchant scions acquire their education from personal tutors, bards, heralds, and noble counselors retained specifically for that purpose by their parents.

True scholarly learning is the preserve of sages, scribes, clerics, and wizards. The nonhuman races of Faerûn, particularly the elves, are a notable exception to that statement, as are human cities or nations that encourage citizens to study with the clergy of deities who promote knowledge and learning.

Adventurers

Any heroic adventurer breaks many of the rules and norms associated with the feudal hierarchy. She is often the champion of the common folk, yet granted access to the highest halls of power as an agent of her lord or king. Generations of good-hearted adventurers have helped make Faerûn a safer and better place to live, and any ruler knows that the best way to solve a sticky problem often involves finding the right adventurer for the job.

By definition, adventurers are well armed and magically capable beings who are incredibly dangerous to their enemies . . . and not always healthy to be around, even for their friends. Lords and merchants tread carefully around adventurers and take steps to defend themselves against a powerful adventurer who suddenly develops a crusading zeal or an appetite for power - typically by retaining skillful and well-paid bodyguards to discourage sudden violence.

Adventurer Companies

Groups of adventurers sometimes form communal associations that share treasure, responsibility, and risk. Adventuring companies stand a better chance of receiving official recognition and licenses from kingdoms, confederations, and other principalities that prefer formalized relations with responsible adventuring parties to unlicensed freebooting by random adventurers. In rare cases, adventuring companies can receive exclusive rights to specific areas, making it legal for them to "discourage" their competition.

Chartered adventurers are considered officers of the realm they serve, with some powers of arrest and protection against the interference of local lords guaranteed by the terms of their charter. For example, most strangers entering a city might be required to surrender or at least peacebond their weapons, but chartered company members are allowed to retain their arms and armor as long as they remain on their good behavior.

Adventurers In Society

Most residents of the Dales, Cormyr, the Western Heartlands, and the North are well disposed toward adventurers of good heart. They know that adventurers live daily with risks they would never be willing to face themselves. The common folk eagerly seek news of travelers regarding great deeds and distant happenings, hoping to glean a hint of what the future might hold for them as well.

An adventurer willing so ally himself with a lord whose attitudes and views coincide with his own gains a powerful patron and a place in society commensurate with the influence and station of his patron. Adventurers inclined to threaten or intimidate the local ruler simply invite trouble. Those who abuse their power are thought of as nothing but powerful bandits, while adventurers who use their poker to help others are blessed as heroes. Adventurers are exceptional people, but they live within societies of everyday people living commonplace lives.

The Concerns of the Mighty

There comes a time when every student and many a passing merchant, farmer, and king, too, demands the same answer of me: Why, O meddler and, mighty mage, do ye not set the crooked straight? Why not strike directly against the evils that threaten Faerûn? Why do not all mighty folk of good heart not simply make everything right?

I've heard that cry so many times. Now hearken, once and for all, to my answers as to why the great and powerful don't fix Toril entire every day.

First, it is not at all certain that those of us with the power or the inclination can even accomplish a tenth of the deed asked of us. The forces arrayed against us are dark and strong indeed. I might surprise Manshbon or old Szass Tam and burn him from the face of Toril - but he might do the same to me. It's a rash and short-lived hero who presses for battle when victory is not assured.

Second, the wise amongst us know that even gods can't foresee all the consequences of their actions - and all of us have seen far too many instances of good things turning out to cause something very bad, or unwanted. We've learned that meddling often does far more harm than good.

Third: Few folk can agree on what is right, what should be done, and what the best end result would be. When ye consider a mighty stroke; be assured that every move is apt to be countered by someone who doesn't like the intended result, is determined to stop it, and is quite prepared to lay waste to you, your kingdom, and anything else necessary to confound you.

Point the fourth: Big changes can seldom be effected by small actions. How much work does it take just to build one house? Rearrange one room? How many simple little actions, then, will it take to destroy one kingdom and raise another - with name, ruler, and societal order of your choice - in its place?

Finally: D'ye think we "mighty ones" are blind? Do we not watch each other, and guess at what each is doing, and reach out and do some little thing that hampers the aims of another great and mighty? We'll never be free of this problem, and that's a good thing. I would cower at the thought of living in any Faerûn where all the mighty and powerful folk agreed perfectly on everything. That's the way of slavery and shackles and armed tyranny ... and if ye'd like to win a bet, wager that ye'll be near the bottom of any such order.

Right. Any more silly questions?

- Elminster of Shadowdale

Language

Common language and culture defines a state just as much as borders, cities, and government do. Each major nonhuman race speaks its own language, and humans seem to generate dozens of languages for no other reason than their lands are so widespread and communications so chancy that language drift occurs over time. Hundreds of human dialects are still spoken daily in Faerûn, although Common serves to overcome all but the most overwhelming obstacles to comprehension.

The oldest languages spoken in Faerûn are nonhuman in origin. Draconic, the speech of dragons, may be the oldest of all. Giant, Elven, and Dwarven are also ancient tongues. The oldest known human languages date back some three to four thousand years. They come from four main cultural groups - Chondathan, Imaskari, Nar, and Netherese - that had their own languages, some of which survive today in altered forms after centuries of intermingling and trade.

The Common Tongue

All speaking peoples, including the humans of various lands, possess a native tongue. In addition, all humans and many nonhumans speak Common as a second language. Common grew from a kind of pidgin Chondathan and is most closely related to that language, but it is far simpler and less expressive. Nuances of speech, naming, and phrasing are better conveyed in the older, more mature languages, since Common is little more than a trade language.

The great advantage of Common, of course, is its prevalence. Everybody in the Heartlands speaks Common well enough to get by in any but the most esoteric conversations. Even in remote areas such as Murghôm and Samarach, just about everybody knows enough Common to speak it badly. They might need to point or pantomime in a pinch, but they can make themselves understood. Natives of widely separated areas are likely to regard each other's accents as strange or even silly, but they still understand each other.

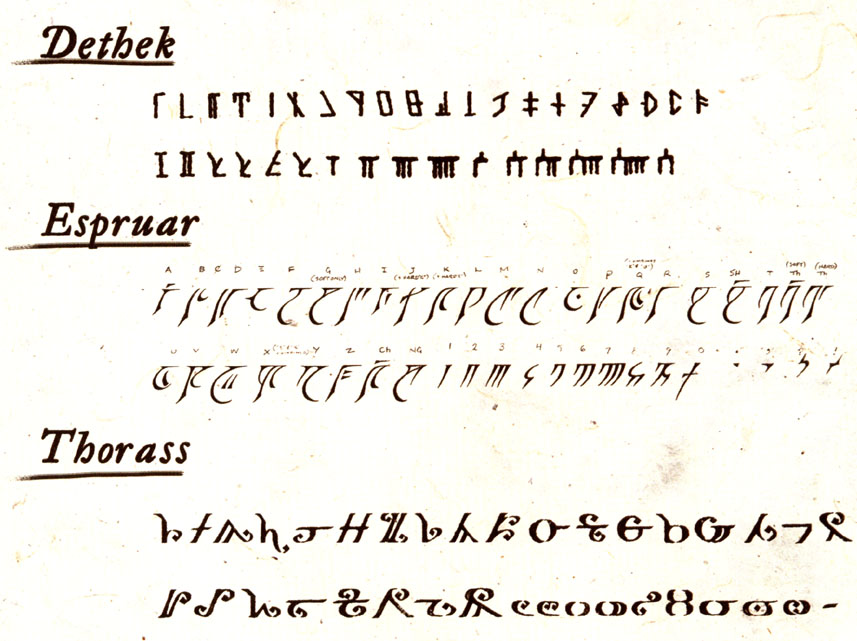

Alphabets

The human and humanoid languages of Faerûn make use of six sets of symbols for writing: Thorass, a human symbology; Espruar, a script invented by the elves; Dethek, runes created by the dwarves; Draconic; the alphabet of dragons; Celestial, imported long ago through contact with good folk from other planes; and Infernal, imported through those outsiders of a fiendish bent.

A scribe whose name is lost to history invented the set of symbols that make up the Thorass alphabet. Thorass is the direct ancestor of today's Common tongue as a spoken language. Though no one speaks Thorass anymore, its alphabet survives as the alphabet of Common and many other tongues.

Espruar is the moon elven alphabet. It was adopted by sun elves, drow, and the other elven peoples thousands of years ago. Its beautiful weaving script flows over jewelry, monuments, and magic items.

Dethek is the dwarven runic script. Dwarves seldom write on that which can perish easily. They inscribe runes on metal sheets or carve in stone. The lines in all Dethek characters are straight to facilitate their being carved in stone. Aside from spaces between words and slashes between sentences, punctuation is ignored. If any part of the script is painted for contrast or emphasis, names of beings and places are picked out in red while the rest of the text is colored black or left as unadorned grooves.

The three remaining scripts, Draconic, Celestial, and Infernal, are beautiful yet alien, since they were designed to serve the needs of beings with thought patterns very different from those of humanoids. However, humans with ancient and strong cultural ties to dragons (and their magic) or beings from far-off planes have occasionally adapted them to transcribe human tongues in addition to the languages they originally served.

Living Languages

Scholars at Candlekeep recognize over eighty distinct active languages on Toril, not including thousands of local dialects of Common, such as Calant, a soft, sing-song variant spoken in the Sword Coast, Kouroou (Chult), or Skaevrym (Sossal). Secret languages such as the druids' hidden speech are not included here, either.

A character's choice of race and region determines her automatic and bonus languages. See Character Regions. However, the following languages are always available as bonus languages to characters, regardless of race or region: Abyssal (clerics), Aquan (water genasi), Auran (air genasi), Celestial (clerics), Common, Draconic (wizards), Dwarven, Elven, Gnome, Goblin, Giant, Gooll, Halfling, Ignan (fire genasi), Infernal (clerics), Ore, Sylvan (druids), Terran (earth genasi), and Undercommoo. Druids also know Druidic in addition to their other languages.

If a character wishes to know a language other than her automatic and bonus languages determined by race, region, and the above list, she must spend skill points on Speak Language to learn it.

Dead Languages

Scholars and researchers of the obscure can name a number of dead languages. These languages are often the antecedents of one or more modern languages, but the original language is so different that it is usually in comprehensible to one fluent in the modern tongue. None of these languages has been a spoken, living language in thousands of years, and it is doubtful that anyone in the world knows their proper pronunciation.

| Language | Alphabet | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Aragrakh | Draconic | Old high wynn |

| Hulgorkyn | Dethek | Archaic ore |

| Loross | Draconic | Netherese noble tongue |

| Netherese | Draconic | A precursor of Halruaan |

| Roushoum | Imaskari | A precursor of Tuigan |

| Seldruin | Hamarfae | Elven high magic |

| Thorass | Thorass | Old Common |

These languages can be recognized by anyone who knows how to read the alphabet the language is written in, but the words are gibberish unless the character used the Speak Language skill to buy the ability to comprehend the dead language or succeeds on a Decipher Script check against DC 25. Because Thorass is archaic Common and still somewhat comprehensible to those who know Common, the DC to read it is only 20. The only way to read something written in Roushoum or Seldruin is to use a comprehend languages spell or to succeed on a Decipher Script check against DC 30, since the alphabets of these languages are no longer in use at all.

| Regional Language | Spoken in ... | Alphabet |

|---|---|---|

| Aglarondan | Aglarond, Altumbel | Espruar |

| Alzhedo | Calimshan | Thorass |

| Chessentan | Chessenta | Thorass |

| Chondathan | Amn, Chondath, Cormyr, the Dalelands, the Dragon Coast, the civilized North, Sembia, the Silver Marches, the Sword Coast, Tethyr, Waterdeep, the Western Heartlands, the Vilhon Reach | Thorass |

| Chultan | Chult | Draconic |

| Common | Everywhere on Faerûn's surface (trade language) | Thorass |

| Damaran | Damara, the Great Dale, Impiltur, the Moonsea, Narfell, Thesk, Vaasa, the Vast | Dethek |

| Dambrathan | Dambrath | Espruar |

| Durpari | Durpar, Estagund, Var, Veldorn | Thorass |

| Halruaan | Halruaa, Nimbral | Draconic |

| Illuskan | Luskan, Mintarn, the Moonshaes, the Savage North (uncivilized areas), Ruathym, the Uthgardt barbarians | Thorass |

| Lantanese | Lantan | Draconic |

| Midani | Zakhara*, the Bedine | Thorass |

| Mulhorandi | Mulhorand, Murghôm, Semphar | Celestial |

| Mulhorandi (var.) | Thay | Infernal |

| Nexalan | Maztica* | Draconic |

| Rashemi | Rashemen | Thorass |

| Serusan | Inner Sea (aquatic trade language) | Aquan |

| Shaaran | Lake of Steam, Lapaliiya, Sespech, the Shaar | Dethek |

| Shou | Kara-Tur* | Draconic |

| Tashalan | Black Jungle, Mhair Jungle, Samarach, Tashalar, Thindol | Dethek |

| Tuigan | Hordelands | Thorass |

| Turmic | Turmish | Thorass |

| Uluik | Great Glacier | Thorass |

| Undercommon | Underdark (trade language) | Espruar |

| Untheric | Unther | Dethek |

| *These other lands on Toril are not in Faerûn. | ||