Cormanthor - Part One

Design: Rick Swan

Editing: James Butler

Interior Art: Daniel Frazier

Cartography: Dennis Kauth

Typography: Nancy J. Kerkstra

Production: Paul Hanchette

Words From an Old Friend

Elminster says that the secret of happiness is having as many interests as stars in the sky, and the only way to find out if something interests you is to see it first hand. To him, that means travel, and plenty of it. "There's more to the world than the backsides of all these trees!" he always yowled at me. "Get out of the woods!"

No thanks. Everything I want is here. Why would I want to leave? To me, traveling means hours of boredom and discomfort, punctuated by an occasional ambush, robbery, or mauling. I've lived all my life in the elven woods. Cormanthor, if you prefer - and I intend to die here some day, preferably later than sooner.

Elminster likes to tease me about my attitude. He calls me "Little Miss Lemon." So I'm sour. It's part of my charm, and I came by it honestly.

I grew up in a tiny elven village called Alyssim, about 50 miles east of Essemore in the Tangled Trees. It was a pretty place, filled with violets and wild roses, but the villagers liked their flowers a lot more than they liked me. As far as they were concerned, I was an embarrassment from day one.

First, I had the audacity to be born half-elven. Half-elves may be common in the rest of the world, but not in Alyssim. I couldn't have stood out more if I'd been born with wings. Though the village elders resisted the urge to drown me in the Elvenflow, they made their displeasure clear by declaring my human father guilty of polluting the race and sentencing him to a decade of hard labor. He fled a day after the sentencing. I never got to meet him.

Second, I had the bad judgment to be born female. In Alyssim society, a woman was considered less useful than a good mule. Those few males who attempted to flaunt this foolish belief in my presence learned to swim a little faster than their much wiser - and silent - friends.

Third, I had the bad taste to reject Alyssim religion. The villagers worshiped Rillifane Rallathil, whom they believed gave them everything from the food in their bellies to the hair in their noses. My mother took a broader view. She worshiped the Sacred Hexad - my mother's term - of Rillifane Raillathil, the Great Mother Chauntea, Silvanus of the Wilderness, Mielikki, the Lady of the Forest, Eldath the Quiet One, and Aerdrie Faenya, goddess of the air. I still worship the Hexad today, fervently and passionately.

I suppose my disgust with the prattle and prejudice of my fellow elves is what nudged me to seek solace with animals and why I eventually became a ranger. Animals don't sell their loyalty for money. Animals know instinctively that life is for enjoyment, a fact that seems to have eluded most humanoid races. The Alyssim elves certainly took any sign of happiness on my part as a sign to make my life more difficult.

I left Alyssim as soon as I was old enough to lace my own boots. I never looked back. Alyssim is long gone now, overrun with weeds - stinkweeds, appropriately enough.

A few years later, I met a human explorer named Ruke Diggot, a young scholar from Mistledale who was studying the butterflies of Cormanthor. He stood as tall and straight as an oak, his smile as bright as the crescent moon. Within a month, we were married. We roamed the woods together for a blissful eleven years until a giant frog leaped from an alder thicket and swallowed him whole.

We had eleven children, one for each year of our marriage. From Ruke, they got common sense and curly red hair. From me, they got stubborn streaks and a love of the wilderness. They're grown now, with families of their own. All still live in these woods.

After Ruke's death, I spent most of the next decade feeling sorry for myself. I wandered the forest from one end to the other and back again, accumulating the information that graces these pages, just to fill the days. My children had lives of their own. I had no community, no friends. I ached for my husband.

Then I met Elminster. I caught him skinny dipping in the Elvenflow, soaping himself vigorously and singing in a voice so tuneless I expected squirrels to pelt him with acorns. When he spotted me, he shrieked like a cat with its tail in a trap, then scrambled for his clothes, red as a spring tomato.

If you've met Elminster, he's probably told you a lot about himself, but I bet he didn't mention a thing about that summer. How he made honey pudding for me on our very first day together. How he braided my hair with daisies. How we [manuscript deleted by Elminster]...

That was - my, that was at least 40 years ago. I've changed since then. My hair's gone gray, and I can't fit into the blouse El made for me.did you know he's good with a needle and thread?

Ordinarily, I couldn't be bothered to write a book like this, not while there are sick bear cubs to feed and grandchildren to take on unicorn rides. How could I refuse you, El? Besides, I've seen too many people die out here - including a couple of my own kin - from carelessness, misinformation, and ignorance.

I hope this helps, and El, look me up next time you get out this way. Bring daisies.

- Lyra Sunrose

Part One: Trees, Trees, and More Trees

You may think you've seen big forests, but you've never seen one that comes within a worg's whisker of Cormanthor.

On a map, it just looks like a green splotch between the Desertsmouth Mountains and the Cold Field. Take a closer look. Cormanthor covers more territory than the Thunder Peaks, and you could plop the Moonsea into here with enough room left over for the Lake of Dragons.

It's dense, too. Put a monkey in a branch just north of Highmoon, and it could swing its way to Elventree without ever setting foot in the grass. You could use the wood to make arrows for every archer from Calimshan to Vaasa, with enough left over to build a boat for all the sailors on the Inner Sea.

The Hexad must have truly loved Cormanthor, for it was the finest forest they ever created. Chauntea made beds of rich black soil, which Aerdrie Faenya fed with sunshine and soft rain. Mielikki and Rillifane Rallathil planted countless species of trees, ranging in size from the knee-high fairy pine to mighty oaks towering four hundred feet. Silvanus nurtured the forest like a loving gardener, shaping each leaf and painting them every color of the rainbow. Aerdrie Faenya sent gentle winds to caress the trees and thunderstorms to strengthen them. Eldath made them heavy with flowers and fruit.

It was a paradise, but like anything too good to be true, it didn't last. Not all of it, anyway. Cormanthor once encompassed a much greater region, stretching from the Storm Horns Mountains to the Sea of Fallen Stars. As cleanly as a scythe shears a wheat stalk, civilization cut it down.

The humanoid natives of the woods - the elves, half-elves, a few human tribes - have always harvested trees for homes, weapons, and trinkets. The forest shrugged off the damage. As the kingdoms of Cormyr and Sembia developed and grew, the forest was forced to surrender. The trees could withstand dozens of axes, but not thousands. The settlers regarded the trees as nothing more than weeds. sturdy weeds, perhaps, but weeds nonetheless. Some elves abandoned the woods for the new cities, others left in the great Retreat to Evermeet. A few die-hards, including yours truly, hung on.

Despite the settlers. shortsightedness - future generations will also need wood for their treasure chests and rowboats, but the settlers apparently didn't consider how long it takes for a new tree to grow - I don't begrudge them their actions. Humans need to build cities like bees need to make hives. If humans are dumb enough to wreck everything in their way.well, that's just their nature. Anyway, they did me a favor by scaring off the elves. Cormanthor is a nicer place to live now than it was before Cormyr and Sembia came along, at least for an old crab like me. Elminster says I'm not only an old crab, but an old fool, that if I think the days of human expansion are gone, I'm out of my mind. Maybe so, but for now, all's quiet. I can't mourn for what was or what might be.

Old Settlements

If you've spent any time at all in or around Cormanthor, you've undoubtedly heard of the four elven communities: Semberholme, the Tangled Trees, the Elven Court, and Myth Drannor. If you're like most people, you've heard the legends and wonder if they're true. On our first night together, Elminster insisted on grilling me about Myth Drannor until I dumped a bowl of honey pudding on his head to shut him up.

As far as I'm concerned, the legends are more interesting than reality. Maybe they used to be bustling centers of art, science and commerce, but now they're mostly crumbling stone and rotten wood. I suggest that you avoid them. Places this famous invariably attract troublemakers. At best, you may run into an elven geezer bent on boring you to tears with stories about the good old days. At worst, you may find monsters so nasty they make dracoliches look like bunny rabbits.

Go if you must, but be careful. If you're looking to get rich, you can find plenty of people to sell you information and treasure maps. I'm not one of them, but I'll tell you - free of charge - about some things you might otherwise miss.

The Elven Court, for instance, is littered with old buildings of every conceivable size and shape, from box-sized shacks to spectacular palaces big enough to hold a convention of storm giants. Most have been picked clean.

You want treasure? Keep going until you get to an oak grove about 50 miles south of Elventree. It's thick with bats, most of them ordinary insect-eaters, with a few assorted azmyths and sinisters. Find an oak whose trunk diameter equals exactly half the wingspan of one of the male sinisters; male Elven Court sinisters have white mouths. Scrape the bark from the oak - the "tree" is solid gold. An elven mage accomplished this before his death, apparently to keep his treasure safe from grave robbers.

Which oak, you ask? Beats me. Good luck.

The hills of Semberholme are still riddled with the limestone caves that the original residents used for shelter. Some contain pools of fresh water fed by underground streams. Don't be put off by the odor. Some smell like spoiled milk and dead fish, but they're all drinkable.

You'll find a scattering of oat fields near the west shore of Lake Sember, which the elves maintained for food and trade. The fields now attract wild horses, especially in the autumn. If you're in the market for a new mount, you could do worse. Be careful though. if even a single horse considers you a threat, expect them all to attack as a herd. A nephew of mine was killed when he spotted a mare drinking from a brook and tried to lasso it. The rest of the herd surrounded and charged. They stomped him so brutally that there was nothing left to bury.

Hundreds of elves still call the Tangled Trees home. Unless you're elven, stay away - they're as ornery as bee-stung badgers and don't take kindly to trespassers. Most prefer to fire arrows first, then ask questions during the funeral. If by circumstance or stupidity you find yourself in these parts, bring along a canary. specifically, one of the emerald throated canaries that nest in the butternut trees along the southwestern shore of the River Duathamper. They're easy to catch. Hold out a handful of lemon or orange peelings and sooner or later, one will land in your palm.

The Tangled Tree elves - some, not all - consider themselves devout worshippers of Rillifane Rallathil. An elven priest by the name of Makk Fireseed has convinced his followers that the canaries are Rillifane's favorite creature; the yellow feathers stand for the sun, the green throat represents the leaves of the trees, or some such nonsense. If you run into a band of elves with a bad disposition, try offering them a Duathamper canary. If you can supply a silver cage or a gold band for its foot, so much the better. The elves may not become your best friends, but with luck, they'll let you pass.

By the way, when traveling through the Tangled Trees, you may notice the occasional oak tree with an outline of a canary carved in the trunk, usually about two feet from the ground. Let it be; it's an elven shrine to Rillifane Rallathil. If you chop it down, tie your horse to it, or even lean against it, a whole flock of canaries won't save your neck. Need convincing? Look up. In the highest branches, you'll see the dangling skulls of previous defilers who mistook the shrine for just another tree.

Somebody could write a book about Myth Drannor - I think Elminster may have tried - but not me. I've made it a point to stay out of Myth Drannor altogether. When I was young and too dumb to know better, I decided to check it out. I had some half-baked notion that I'd find a secret cache of gold, as if the same idea hadn't occurred to every avaricious soul from here to Amn. To be on the safe side, I recruited a pair of black bears to go with me.

When we got within ten miles of the place, the bears were growling and snorting. Every few minutes, they stopped to sniff the air, then shook their heads in confusion before reluctantly padding on. By the time we reached the outskirts of the city, one bear had already bolted into the brush, scrambling in the general direction of Anauroch as fast as his paws could take him. The other bear was whining like a whipped kitten, digging his claws into the ground and refusing to move. I had my arms around his neck and was trying to drag him forward when I heard something thunder overhead. A red dragon was roaring out of Myth Drannor, wings beating furiously, its face wrenched in stark terror!

I didn't wait to see what was chasing it. I dived into a clump of brambles, squirming underneath as far as I could, ignoring the thorns that ripped my back. I cowered there shaking, waiting for the end. The bear bolted into the trees and disappeared.

Gradually, the roar receded. I stayed where I was, listening to the crickets chirp and leaves rustle. Three hours later, I wriggled out of the brambles, half expecting some hellish monstrosity to swoop from above and carry me away in its claws. It didn't happen, but I kept one eye cocked toward the sky all the way home, just in case.

I never found out what was chasing the red dragon. I hope I never do.

So what do you need to know about Myth Drannor? Just this: Ages ago, they called it the City of Love, an elven paradise where beauty reigned and peace prevailed. Then came the Army of Darkness, an onslaught of fiends and brutes bent on grinding the city to dust. The elves defended themselves by erecting shields of magic and recruiting dragon guardians. In the end, the effort failed and the kingdom collapsed. The elves fled, leaving behind a graveyard of collapsed buildings and abandoned dreams. Myth Drannor now exists as a refuge for predators and a breeding ground for monsters. The City of Love? The City of Death is more like it.

Anyone who rests his neck on the executioner's block deserves to have his head removed. I have no advice for navigating Myth Drannor, nor suggestions for surviving its many dangers. I will, however, share some observations about how Myth Drannor has affected the rest of Cormanthor.

So powerful is the magic of Myth Drannor that it's spilled over into the surrounding countryside, drenching the creatures, the trees, and the very soil. I don't pretend to understand the reasons for or even the extent of these effects. To be honest, I probably wouldn't have realized that the elven woods were so different from forests elsewhere in the world if Elminster hadn't educated me. Now I'm convinced. You need to know about them so you don't think you're going crazy when your potion of healing goes flat or you see a chicken trying to eat a mouse.

According to Elminster, the magic of Myth Drannor has had three major effects on Cormanthor. Briefly:

The Weather: Summers aren't as hot and winters aren't as cold as they ought to be. The temperature differences between Cormanthor and similar forests are subtle, only a few degrees in some instances. Normal factors - shade, precipitation, winds - can't account for the favorable climate, which prevails nearly all year long.

Diversity: The number of animal and plant species in Cormanthor far exceeds that of other temperate woodlands. Virtually any organism that could survive in a forest environment can be found here. You won't find locathah or frost giants, but such otherwise rare creatures as bulettes and chimerae turn up in surprising numbers. We have far more than our share of oddities, many of them refugees from Myth Drannor.

Edgelands: They don't look unusual, but these patches of wilderness scattered throughout Cormanthor affect magic and its wielders in extraordinary ways. Elminster theorizes that the edgelands were created by magical energies that drifted from the mythal, the web-work of living magic enveloping Myth Drannor. I'll take his word for it. Suffice to say, if you depend on spells to rustle up food or defend yourself from angry ogres, don't camp in the edgelands. We'll get into the details of the edgelands a little later. Right now, let's talk about where you can take a bath.

Two Rivers

Two major rivers wind through the elven woods: the Duathamper, or the Elvenflow, which runs along the southwestern border, and the Ashaba, which cuts the forest in half from Shadowdale to just east of Semberholme. Both are suitable for swimming, boating, and bathing, though I prefer the Elvenflow for the latter, as it provides more privacy. Of course, that's what Elminster thought, too; he was soaping himself about 10 miles north of Hammer Ford when I saw him - all of him - for the first time.

Though most maps don't show them, dozens of narrow streams branch off the Elvenflow, many ending in small ponds. The streams usually run clear and are rarely more than a few inches deep, perfect for cooling your feet on a hot day.

You'll never touch bottom in most sections of the Elvenflow proper. I tied a stone to a 30-foot vine to measure the depth at various points, and I usually ran out of vine before I ran out of water. It's also wide, hundreds of yards most of the way, but every few miles it narrows and shallows out enough to wade across. Black granite bridges span the river at three places, courtesy of some enterprising elves - I didn't say they were all bad.

The Hexad must have made the Elvenflow for fishing, as they stocked it with bass, catfish, and trout, some as big as a ponies. The fish are so thick that a raccoon could cross the river by walking on their backs. For fishing, a cane pole or even a simple hand line will suffice. With fish practically flinging themselves ashore, if you can't catch your dinner, you deserve to go hungry.

Bait? Worms, animal fat, or even a scrap of colored cloth will work. If you want to land the big ones, try the button fungus that grows on the undersides of birch limbs; it looks like tiny mushrooms covered with brown fur and smells like month-old cheese. The fish love it, especially those pudgy trout.

The Ashaba is as wide as the Elvenflow and nearly as deep. I know of only one granite bridge, about 30 miles south of Mistledale, but it's in bad shape thanks to a nearsighted black dragon who mistook it for a rival and tried to smash it to pieces. The banks of the Ashaba slope much more sharply than those of the Elvenflow, a straight drop in some places.

If you're lucky, you might spot an orc on his belly, leaning over the bank to hand-fish. Watch long enough, and you may see him lean too far and fall in. If you're really lucky, you might see a giant carp break the surface and suck him down like a worm. The carp around here, by the way, have perpetually empty stomachs. They've been known to chew up canoes and pick their teeth with the oars.

Truth to tell, it wouldn't bother me if the carp grew legs and chased down every orc south of Ashabenford. The Ashaba used to be as rich a fishing ground as the Elvenflow. No more. On a good day, a patient fisherman can still snag enough walleye and bullhead to feed his family, particularly in the southern waters. Up north, in a section Elminster refers to as "The Barrens," you can cast your line for hours on end and have nothing to show for effort except a skinny sunfish the size of your little finger. The orcs overworked the northern section of the river, using trawling nets to scoop up fish by the hundreds. To get rid of the giant carp, they dumped in wagonloads of a special herbal poison. Not only did the poison fail to get rid of the carp, it turned them black and made them meaner.

The orcs' attempt at wildlife management decimated the game fish population. For nearly a year, the waters reeked so badly from dead fish that you could smell it ten miles away. The water has cleared up some, but the carp are still practicing a little management of their own, so be careful when wading out into the Ashaba.

A pair of streams in the southern woods, the Semberflow and the Deeping, also provide relief for the thirsty traveler. Their crystal waters teem with bass and catfish in quantities rivaling the Elvenflow. It is an otherwise unremarkable area, drawing too many human tourists for my taste.

The westernmost stretch of the Deeping, however, serves as a spawning ground for a tasty variety of freshwater shrimp. The Deeping shrimp, nearly a foot long and brilliant red, can be caught by dragging nets along the river bed. The halflings living in the area manufacture special trawling nets for just this purpose, consisting of finely-woven mesh attached to weighted boards. The boards are buoyant enough to make for easy trawling, but not heavy enough to sink. The halflings are excellent net-makers, but dismal businessmen. You should be able to buy a net for a couple of silver pieces. As a bonus, the dried shrimp shells emit a soft pink light for up to two days and can be used to mark trails.

Weather

A forest the size of Cormanthor needs the right amount of rain and sunshine. Too much water washes away delicate seedlings and topsoil. If there's not enough water, the soil dries up and everything starts to die. Excessive heat causes the ground water to evaporate and plants to wither.

Fortunately, the climate couldn't be better. In part, this is due to the moderating effect of the Myth Drannor energies, but it's also due to the way the Hexad designed the terrain. According to Elminster, the sun strikes Cormanthor at precisely the right angle to warm the trees without scorching them. Precipitation falls lightly but steadily all year long, keeping the ground moist and the air cool. Thanks to the forest's sheltering canopy, which provides both shade and protection from harsh winds, we're spared the temperature extremes of the surrounding areas. A fur jacket and a good pair of leather trousers, and I'm cozy on the coldest winter day.

In short, compared to other regions - especially other forests - Cormanthor has warmer winters, fewer gale-force winds, higher humidity, and more than its share of rain. As to how hot it gets and how much rain falls, I've never kept track, but Elminster has, and he's slipped some figures in here somewhere. Those figures aside, I'd say that if you spend a couple of weeks in these parts, plan on getting rained on a day or two. Otherwise, enjoy the sunshine - we've got plenty of it.

Climatic Averages for Cormanthor

| Temperature (Spring) | 72° F. |

| Temperature (Summer) | 78° F. |

| Temperature (Autumn) | 65° F. |

| Temperature (Winter) | 43° F. |

| Low Temperature/Year | 15° F. |

| High Temperature/Year | 86° F. |

| Annual Precipitation | 70 inches |

| Days With Snow on Ground | 25 days |

Daily Weather

To determine the temperature on a particular day, find the average temperature of the current season listed in the Climatic Averages section above. Roll 1d10. If the result is odd, subtract it from the average. If the result is even, add it to the average. For example, if the season is autumn and the roll is 7, the temperature is 58° (65 - 7).

To determine the prevailing weather, roll 1d20 and consult the following table.

Prevailing Weather in Cormanthor

| d20 Roll | Weather* |

| 1-7 | Clear |

| 8-11 | Partly Cloudy |

| 12-15 | Overcast |

| 16-19 | Precipitation1 |

| 20 | Extreme weather2 |

| *For random determination of wind velocity, roll 1d6; 1-3 = less than 10 mph, 4-5 = 10-20 mph, 6 = more than 20 mph. To determine the direction of the wind, roll 1d4; 1 = north, 2 = east, 3 = south, 4 = west.

¹Roll 1d6; 1-2 = up to 1/2 inch; 3-4 = 1/2 to 1 inch, 5 = 1-2 inches, 6 = more than 2 inches. ²Hailstorm, blizzard, heavy fog, tornado, etc., as decided by the DM. | |

The DM may make adjustments to this list when special events exist (such as magical manipulation of the weather), when unusual conditions prevail (such as long droughts), or in exotic terrain (such as mountain peaks).

Seasons

Unlike Anauroch or the Great Glacier, where every miserable day is pretty much like the next, Cormanthor experiences distinct seasons. The inhabitants adapt accordingly; bears hibernate in the winter, caterpillars spin cocoons in the spring, wild ducks migrate in the autumn. Though rare, a bad stretch of weather can wreak havoc on the animals.

Eighteen years ago, we experienced a summer drought that just about killed off the rye grass, which in turn starved most of the region's red deer. The autumn before last hit us with an earlier-than-usual frost, destroying nearly all the wild flowers and berry bushes north of Highmoon, which wiped out most of the rabbits and gophers. The leucrotta in the area had less to eat, and turned on Casckel, a village of peaceful halflings. By spring, there was nothing left of Casckel but empty huts and halfling bones.

Fortunately, seasons tend to be pretty much the same from year to year. This summer should be about as warm as the one before, and I'd be surprised if the amount of rain varies more than an inch or two from spring to spring.

Spring comes calling in Ches and lasts until Flamerule. Thawing begins in the first few weeks of Ches, and by mid-Tarsakh the cottonwood trees are already sprouting buds and daffodils are beginning to flower. The lengthening day, providing nearly 16 hours of direct sunlight by Flamerule, allows vegetation to grow quickly; most seedlings mature before summer begins. Rain is frequent but light. Skies remain bright and clear during most spring storms.

Summer arrives in Eleasias and extends through Marpenoth. Temperatures peak in late Eleasias, but we experience only a handful of days I'd consider uncomfortable. For perhaps half of Eleasias, an old horse might risk exhaustion from overheating, or a traveler might find the shade of an oak tree more appealing than the arms of her lover. Calm winds and blue skies predominate, but you should stay on guard for thunderstorms. A summer storm can come and go in an hour's time, pounding the earth with sheets of rain and shattering trees with lightning spears. Pockets of fog often shroud long stretches of the forest, particularly near the northern Elvenflow. Oppressive humidity, common in Eleint, can sap the strength of the mightiest warrior; wear loose clothes, drink plenty of water, and if possible, travel at night.

Autumn, occurring in Uktar and Nightal, brings lower temperatures, shorter days, and an avalanche of falling leaves that hides most of the ground within a few weeks. Rain falls infrequently, but winds blow almost daily, often with enough force to flip the hat from your head or stir up a whirlwind of fallen leaves. The first killing frost, usually arriving in the final days of Nightal, marks the beginning of winter.

Winter consists of the months of Hammer and Alturiak. Hammer tends to be dry and cool, but by early Alturiak, most of the forest has been blanketed by an inch or two of snow. Temperatures remain cold but tolerable. Icicles dangle from bare limbs of oaks, and pheasants huddle beneath huckleberry bushes for warmth.

Don't look for bears or grasshoppers; they're sound asleep, the former in secluded caves, the latter in rotted stumps. Thick, fluffy fur makes rabbits and badgers appear larger than normal. The Semberholme ferret, brown in the spring, now sports a white coat to make him less visible to hungry wolves. You may see a jackalwere rubbing pyrolisk bones together to melt the ice from its paws. Scare away the jackalwere and steal the bones. You can't start a fire with them, but stick them in your sleeping bag at night and they'll keep you toasty.

Adaptations

Ever heard of the communal tower east of Suzail that looked like twenty brick houses piled on top of each other? The bottom layers were reserved for laborers and other common folk while the highest levels.the ones closest to the gods.were home to rich merchants and big shots. A great idea, until a stiff wind blowing off the Lake of Dragons leveled it like a kid swatting a stack of building blocks.

Cormanthor is like that tower, only without the snobbery - and it's a lot sturdier. The height of the trees, hundreds of feet in some places, offers numerous living environments, one atop the other. High-flying falcons make nests in the tree tops. In the branches below, owls live in the hollows, squirrels snooze in the limbs. All manner of animals, ranging from tiny mice to lumbering aurumvorax, lair in the shaded meadows and valleys. Worms and beetles feast on the decayed matter in the ground, much of it derived from rotting leaves.

Cormanthor boasts a good food supply, plenty of water, and ample living space. Still, the creatures who have thrived are those who have enhanced their survival chances with physical adaptations, such as:

Coloration: A chipmunk that glows in the dark or a rabbit with bright red ears might as well hang a sign around its neck that says, "Eat Me." Most species are colored shades of brown, gray, and green, the better to blend in with the surrounding terrain. Some, like the naga and the boa constrictor, sport patterns of blotches for camouflage.

Senses: With so many trees and bushes for hiding places, predators can't rely on eyesight alone to locate their prey. Most forest creatures, predators and prey alike, have sharper-than-average senses of smell and hearing. A behir can distinguish between the scents of a raccoon and a possum at 100 yards. A giant black squirrel can hear a constrictor slithering in the next tree. Likewise, forest dwellers observe a strict code of silence so as not to draw attention to themselves; you will hear few roars, hisses, or tweets, even if surrounded by a zoo full of creatures.

Movement: Because moving through woods this dense can be difficult, maneuverability is valued more than speed, climbing more than flight. Antelope and similarly slender herd animals capable of darting around trees do well; bulky buffalo are better suited to the open ground. Claws for climbing are favored over claws that tear and shred. Woodpeckers and wrens who can swoop through webs of branches fare better than giant eagles.

The Cormanthor Woods

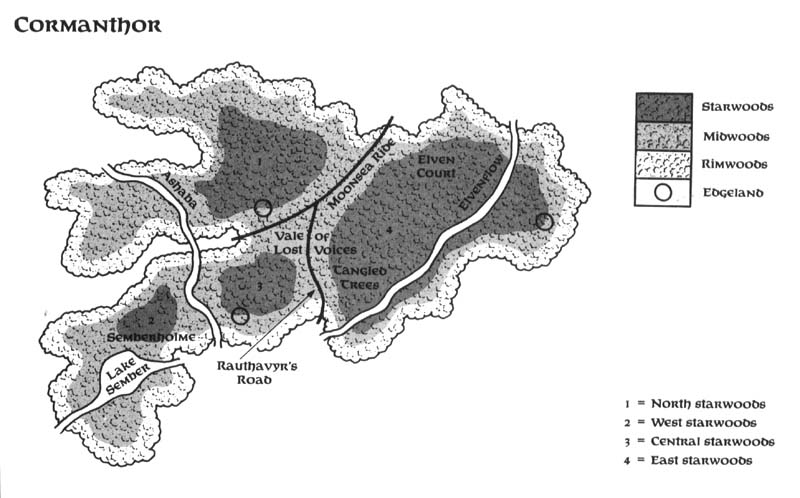

Although many consider Cormanthor to be one big forest, it's actually made up of four forests; Semberholme, the Elven Court, the Tangled Trees, and the Vale of Lost Voices. I've divided Cormanthor up into three areas I call the rimwood, the midwood and the starwood. Admittedly, it's hard to tell where one ends and the next begins, but if you know what to look for, you'll know where you are.

What do you look for? What else? You look for trees. The rimwood consists mainly of pines. The midwood are predominantly white ash and beech. Gigantic oaks and maple make up most of the star- wood. The farther into Cormanthor you go, the denser the vegetation - the rimwood are relatively barren, the starwood are as thick as a jungle.

Rimwood: The rimwood serves as a 10-20 mile border between the elven woods and the rest of the world. Because of the sandy, mineral-poor soil, the rimwood supports little vegetation. Blueridge and needleleaf pines, the primary species of trees, seldom exceed 20 feet and are spaced wide apart; you'll look all day to find two trees whose branches touch each other. The pines continually drop needles that are slow to decompose, inhibiting the growth of other plant life. Softwood ferns, brownish in color and as tough as shoe leather, sprout near the pines, but that's about it. Clumps of wiregrass adorn a few hillsides, as do some droopy willows and stubby spruces.

Because of the lack of vegetation, the area attracts few herbivores, which also accounts for the absence of meat-eaters. You might see a solitary wolf wandering about, or a tortoise pawing the dirt for grubs, but few animals settle permanently in the rimwood. With the lush midwood a few miles away, why would they?

Insects flourish in the rimwood, however, since there aren't many creatures who want to eat them. Beetles scuttle down hillsides like an avalanche of black pebbles. Mosquitoes swarm in clouds so thick you can barely see the sky. Many a traveler who's camped in the rimwood has awakened the following morning with her tent infested with red ants or her sleeping bag crawling with lice.

After a long day's journey through the rimwood, I remember seeing what I thought was an apple tree, heavy with plump fruit. My mouth watered at the thought of apple dumplings, and I rode toward the tree as fast as my horse would carry me. Turned out that it wasn't an apple tree at all, but a pine filled with red leafhopper larvae, hanging from the limbs in squirming clusters.

Aside from its usefulness as an insect haven, the rimwood acts as a buffer zone. It discourages animals from wandering out of the midwood, and makes travelers from the outlands think twice about taking shortcuts through Cormanthor. The major roadways winding through the rimwood - including Rauthauvyr's Road, Moonsea Ride, Moander's Road, and Halfaxe Trail - remain relatively free of pests. You can use them without fear of waking up with a mama tick laying eggs in your hair.

Midwood: Just under half of Cormanthor can be considered the midwood. These are the trees separate ing the rimwood from the starwood, including a thick stretch along the Moonsea Ride that cuts Cormanthor in two. So dense is the midwood that a high-flying bird would be looking down on a sea of solid green. If the bird had bad eyes, it might think the midwood to be a single, sprawling tree.

That bird would be surprised to discover how diverse the midwood truly is, as its rich soil supports hundreds of species of trees, flowers, and plants. White ash and beeches line the gentle valleys along the Ashaba. Chestnuts and red maples crowd the hills north of Mistledale. Vast meadows near Essemore blossom with honeysuckles and snapdragons, bordered by groves of cherry trees and blue cedars. Ivory moss and moonfern decorate groves of alders, hickories, and bitternuts.

Tree trunks provide homes for giant constrictors, while rotting logs give shelter to salamanders and scorpions. Thrushes, cuckoos, and swallows nest in the limbs. The hammering of woodpeckers mingles with the sweet singing of bluebirds. A traveler setting up camp under a canopy of redbud trees might be startled to discover an audience of curious squirrels and warthogs. The traveler may also be puzzled by some of the odd vegetation. A few examples:

Beetle palm trees, named for the black bark that looks like a beetle's shell, grow to heights of 100 feet or more. Clusters of spindly, leafless branches crown the otherwise smooth trunks. The wood contains oily deposits that make it exceptionally flammable. It burns nearly three times as long as other types of wood and produces about half the amount of smoke.

Foxberries, resembling bright yellow grapes, grow on snaky vines found throughout the midwood, typically near beech trees. Foxberries are greasy to the touch and smell like cooked steak. One of the world's few fruits digestible by carnivores, they make an acceptable meal for wolves and other meat-eaters in times of scarce game. Humans can eat them, too, but don't be misled by the aroma.they taste like dirt.

Roseneedle pines thrive along the banks of the Ashaba, growing there the year round. They resemble miniature evergreens, seldom exceeding three feet tall. A roselike blossom, pink or white, sprouts from the end of each tiny needle. A roseneedle's roots extend ten or more feet into the ground, each ending in a fat tuber the size of a potato. Chunks of the tubers make excellent fishing bait; a fisherwoman can easily double her day's catch when using them.

Starwood: I came up with the name when I was settling under a maple tree to go to sleep. The maple was so high, it looked like its branches could pierce the stars.

Okay, so the trees aren't really that high, but they're certainly impressive. I'd guess the maples average 200 feet with some of the taller oaks being twice that. If an oak trunk were hollow, it could hold a small farmhouse.

The starwood consists of four distinct areas. All have towering oaks, hickories, and maples, but each also has its own signature species. West starwood, the area containing Semberholme, boasts thick groves of poplar and gum trees. Spruce and hemlock are common in the central starwood, west of the Ashaba. East starwood, roughly divided into the Elven Court and Tangled Trees regions, feature firs and elms, particularly where the starwood border the midwood. Cedars line the perimeter of the North starwood, home to Myth Drannor.

The starwood soil, as moist as that in the midwood but nearly black, gives rise to all variety of shrubs and thick grasses. The dense underbrush can make traveling difficult. The waist-high wood ferns are as thick as corn stalks, and traversing the carpets of mushy peat feels like wading through mud. Gray mist permeates much of the forest, particularly in the north and east, reducing vision to a few hundred feet. The humid air encourages the growth of lichens and mosses, which drip from tree branches like shredded velvet.

The profusion of grasses and brush supply an endless food source for grazers, such as elk and deer. Well fed manticores sleep on beds of violets, owls chase screeching finches, and wood rats scramble for the cover of zebra grass. Ground-dwellers include both normal and gargantuan porcupines, skunks, and weasels. The fog-shrouded groves of the North and East starwood conceal roving packs of dire wolves. A careless traveler may mistake an emerald constrictor for a mossy tree branch.

As in the midwood, much of the starwood vegetation may be unfamiliar. For example:

Medquat is a crimson lichen found inside hollow logs, particularly camphor. The soft lichen tastes like lemons and is highly prized by Cormyr gourmets. Be careful when groping around in camphor logs; scorpions adore the scent of medquat and like to cover themselves in it.

Chime oak trees thrive in the northern sections of the East starwood. They resemble normal oak trees made of clear glass. Aside from their appearance, chime oaks are indistinguishable from other oaks; birds nest in their branches, they sprout and grow from seedlings, their limbs can be cut and burned for firewood. Unlike normal oaks, however, chime oaks don't lose their leaves in the autumn. Instead, the leaves freeze solid, remaining frozen throughout the autumn and winter until they thaw in the spring. Light breezes cause the frozen leaves to tinkle like wind chimes, producing a soothing, pleasant sound especially attractive to basilisks. These creatures may be found curled up near the trunks, eyes closed, completely relaxed.

Hinnies are forest flowers that look like giant buttercups, 10 feet in diameter, with bright blue petals. Normally, a hinnie's petals are closed tight, giving it the appearance of a huge ball. The closed petals protect a pool of sweet nectar, two or three inches deep. Any attempt to pry the petals apart, pierce them with a sword, or otherwise gain access to the nectar by force causes the hinnie to crumble to dust and its nectar to instantly evaporate. The petals open by themselves for one day in the first week of spring. It's also possible to open the petals by warming them, such as by holding a torch near the petals or building a small fire next to the base. This must be done carefully. If the hinnie gets too hot, it ignites and disintegrates. If a traveler manages to open a hinnie, or is fortunate enough to find one open in the spring, he may sit in its pool and allow the nectar to be absorbed into his body. The results are usually beneficial, but not always. A few years ago, a sister-in-law of mine was found floating face-down in a hinnie pool, the blood drained from her body.

Worth the risk? Not for me.

Hinnie Nectar Effects

A character may attempt to open a closed hinnie as described in the text, using either natural or magical heat sources. If the heat is applied directly to any part of the plant, however, the hinnie automatically disintegrates. Otherwise, roll 1d4; 1 = the plant disintegrates, 2-4 = the petals open.

To be affected by the nectar, a character must sit in the pool for 10 rounds. At the end of this period, all of the nectar will be absorbed into his body; there is enough nectar in a hinnie to affect a single character. It takes about a year for the hinnie to replenish the nectar supply.

To determine the effects of the nectar, roll 1d10 and consult the following table:

| d10 Roll | Effect |

| 1-4 | No effect |

| 5-6 | Can speak with plants (as per the spell) at will for the next 1-4 hours. |

| 7 | Can fly, as a potion of flying. |

| 8 | Skin toughens, giving character AC 12, even without armor; effect lasts 1-2 days. |

| 9 | Skin turns blue; character suffers -2 penalty to Charisma checks; effect lasts for 1-2 days. |

| 10 | All blood evaporates from character's body; character dies unless he successfully saves (Fort DC 10), in which case he retains 1 hit point. |

Edgelands

My first encounter with the edgelands came 44 summers ago. I was exploring the midwood south of Elventree, looking for a place where my niece could set up her refuge for abandoned centaur colts. Seven weeks of searching had been in vain. The land was simply too barren for centaurs, despite the abundance of sunshine and clean brooks.

Another long day was coming to an end. Misha, my wolf cub companion, was hungry and in a bad mood. Rabbits and gophers were scarce, and if Misha didn't get something to eat soon, I was afraid she might develop a craving for horse flesh. I had only one horse, an old mare named Geldi, and I needed to keep her flesh attached to her bones if I was going to get home.

I cast locate plants and animals, hoping to scrounge up some foxberries for Misha, who was now circling an increasingly uncomfortable Geldi. Then the oddest thing happened.

The spell fizzled.

I've cast this particular spell hundreds of times, and I can count on one hand the number of times it failed. Maybe I was more tired than I thought. I tried it again.

Another dud.

I sat in the grass, confused and - I'll admit it - a little scared. I reviewed the spell in my head, trying to recall if I'd left out a step, when I saw something that made me forget what I was trying to remember. Not five feet away from me, Misha was munching sunflowers, pulling petals from stems and chewing them up as if it were the most natural thing in the world. Behind her, Geldi was kicking at a chipmunk. The chipmunk lunged like a cobra, determined to take a chunk out of Geldi's leg.

I shooed away the chipmunk and gathered Misha in my arms, a sunflower stem drooping from her mouth. I mounted Geldi and we galloped away. My niece would have to find her own refuge.

A month later, I told Elminster about my experience. "You're not alone," he said. A cottonmouth snake near the rimwood east of Semberholme had choked to death trying to swallow an apple. North of Highmoon, grasshoppers were seen feasting on the corpse of a cow.

Elminster explained that all of these were natural events - natural, that is, for Cormanthor. Apparently, energy drifts from Myth Drannor were creating regions where magic goes haywire and animal diets are turned upside down. He called these regions "Edgelands," as they only occurred on the borders of two different forests, say, a stretch between the rimwood and the midwood.

Casual inspection of these areas reveal nothing out of the ordinary. Fortunately, they don't last. Elminster says that an edgeland appears in the early spring and vanishes when the first autumn frost arrives. It may or may not reappear in the same place the following spring; usually, it doesn't. He has no idea how many edgelands exist at any given time, but says he'd be surprised if there were more than three or four.

So how do you identify an edgeland? Here are some signs. Not all apply to every edgeland, but if you notice more than one, I'd assume the worst. The area faintly radiates magic. (All edgelands do this.) . Spells don't work the way they should, or they don't work at all. The same for magical items. The diets of small animals are off-kilter; herbivores eat meat, carnivores eat fruit. The area experiences unusual weather effects; raindrops feel warm, a breeze abruptly changes direction, a snow flurry blows up on a summer day.

Aside from some inconvenience - it's frustrating not to be able to cast spells, but hardly the end of the world - what's so bad about an edgeland? Well, consider the ramifications of a swarm of bees with a craving for meat - and you're the only meat available. Stay on your toes when crossing from one forest into another, and if you see a squirrel licking its lips, get out fast.

More About Edgelands

An edgeland may occur in any area of Cormanthor where two forests share a border (a rimwood and a midwood, or a midwood and a starwood).

An edgeland can be any size, but it usually encompasses a roughly circular area, no more than 60 miles in diameter.

An edgeland arises in early spring and disappears when the first frost occurs in early autumn. In most cases, it will not reoccur in the same area the following year. In any given spring or summer, the elven woods typically has two or three active edgelands.

An edgelands may have any or all of the following features, as determined by the DM:

Unusual weather: See text for examples.

Dead magic: No magic, including magic-like monster powers and any psionic powers that affect objects outside the body of the user, operates here. At the DM's option, other magical prohibitions and modifications, such as wild magic, may also occur; these effects duplicate those associated with the mythal of Myth Drannor (see the Ruins of Myth Drannor boxed set for details).

Modified diets for animals: All nonmagical animals in the area with 1 HD or less are affected. Herbivores eat meat, carnivores eat plants, omnivores eat anything other than their normal diet (a piglet, for instance, may eat nothing but ants). The DM decides exactly which animals are affected, as well as the nature of their new diets.

An animal must be capable of getting its new food into its mouth and swallowing it; a gopher can't eat rocks, a butterfly can't eat an elephant. The magic in the area also affects the animals. physiology, allowing them to digest their unusual meals. The magic doesn't affect the animals' behavior, though starving animals may be willing to attack anything that looks edible; meat-eating sparrows might attack frogs, carnivorous field mice might attack humans.

Beware of the Dog

You know enough not to grab a chimera by the tail or poke a sleeping wyvern with a stick. You also know to expect the unexpected when encountering monsters in the wilderness - otherwise, you wouldn't be reading this book.

Remember that so-called "normal" animals can be just as dangerous as the monstrous ones, particularly those living in the relative isolation of Cormanthor. The less contact animals have with humans, the less they fear them. Some animals are merely curious, like an owl who eyes you from a tree top or a raccoon who joins you for a swim. A few are even friendly, such as the parrot who may flutter out of an elm tree to perch on your shoulder and hitchhike for an afternoon. Most animals are suspicious at best, hostile at worst. After all, this is their territory you're invading.

Consider, for example, the wild dog, normally skittish around humans unless starving or provoked. A particular Cormanthor version, a tough, sinewy canine recognizable by its mottled hide, has a foul temper. If awoken by a thunderstorm, a Cormanthor wild dog will snarl and snap at the raindrops. If it survives a hunter's attack, it will track the hunter for weeks. One such vengeful dog tracked a hunter all the way to Arabel, chewed its way into the hunter's bedroom door, then killed the hunter in bed. Though omnivorous, the wild dog prefers the flesh of mammals, and makes no distinction between a baby opossum and a human infant.

It's unclear whether the black or brown bear is more vicious. The black is smaller and faster, the brown larger and stronger. Both are relentless killers. Cormanthor bears consider humans just another type of monkey, annoying and easily dispatched. The bears prefer blueberries and gooseberries to most other food, but when supplies are low, particularly in mid-to-late autumn, they'll eat anything that walks, flies, or crawls. A hungry bear will knock down your horse with a swat of its paw, chase you up a tree, and break your sword in two with a single snap of its jaws.

Interestingly, I've probably heard of more unprovoked attacks from wild boars than any other "normal" animal within Cormanthor. Our boars seem to be born mean; one of my sons reported seeing a litter of newborns rip out the throat of their own mother. Unlike the omnivorous boars elsewhere in the world, Cormanthor boars eat nothing but meat, and they're hungry 24 hours a day. Boars will excavate graves to get to the corpses and swim across rivers to attack boats.

Finally, consider the story of the young elf who discovered a rabbit outside of Myth Drannor. Except for the red fur and bright green eyes, it resembled and behaved like a normal rabbit. The elf put the rabbit inside his coat, where it snuggled against his chest, content and docile. He brought the rabbit home to his family and showed it to his younger brothers and sisters, who fed it clover and stroked its soft fur. That night, he took the rabbit to his grandmother, who shrieked in terror when she recognized the animal for what it really was. The shriek startled the rabbit, causing three spines on its stomach to become erect. The spines pierced the elf's arm, and he fell to the ground, unconscious. He died within an hour.