Cormanthor - Part Two: Monsters

Elminster always says that the first step to knowledge is admitting how little you know. I always say, if you're knowledgeable too often, people will expect you to be that way all the time.

We're probably both right.

If you think you're as smart as you need to be, you're free to ignore the following information. The last person, however, who declined to take me seriously wound up as powder in a bulette nest.

Powder?

Bulette nest?

Maybe you do have a few things to learn!

Aurumvorax

I sprained my ankle so badly I had to use a crutch for a month because of an aurumvorax. The rimwood plains east of the River Lis are riddled with aurumvorax holes. Most of the holes are overgrown with weeds and wild flowers, making them just about impossible to see.

I was chasing a sand hen, a rare type of quail that makes the best soup stock you've ever tasted. It was inches from my fingers when I stepped in an aurumvorax hole. I slammed to the ground, my body going one direction, my foot in another. Howling in pain, I gripped my twisted ankle and watched the sand hen trot off into the brush, cackling with glee.

It could've been worse. The hole could've contained an actual aurumvorax, in which case a sprained ankle would've been the least of my problems. I've seen an aurumvorax strip the flesh from a war horse, and it can hold its own in a fight with a chimera.

The odds, however, of encountering an actual aurumvorax in Cormanthor are about as slim as a ruby dropping out of the sky and bouncing off your head. They're here, of course - I can show you the holes - you just never see them. I've always felt that aurumvorax spend half their waking hours looking for food, the other half trying to find a way out of Cormanthor.

You see, aurumvorax aren't native to Cormanthor. They don't belong here, and they don't particularly like it here, either. For one thing, they're the wrong color for life in a green forest; their golden hides make them stand out like coal on a snow drift. There's little for them to eat; Cormanthor has plenty of mice and gooseberries, but not much gold.

A group of avaricious treasure hunters from Ylraphon introduced aurumvorax to the elven woods three centuries ago. Rumors of gold lured the hunters to the eastern rimwood, and they brought six pair of aurumvorax to sniff it out. The aurumvorax went to work the moment they were released, hungrily digging up rich veins in the hills and plains, gorging on ore while the hunters congratulated themselves on their brilliance.

Unfortunately, the aurumvorax had no intention of sharing. When a hunter attempted to examine one of the gold veins, an aurumvorax sprang, sinking its jaws in the hunter's back. In short order, the aurumvorax polished off the remaining hunters, then returned to the business of excavating their glittery cuisine.

With so much to eat and few predators to bother them, the aurumvorax multiplied like rabbits. Within a decade, they had pretty much depleted the gold, turning the plains of the eastern rimwood into a sea of holes. They spread west, searching for gold in the midwood, then north and south, hoping to find deposits like those in the eastern rimwood. Unfortunately, gold was scarce - the rich deposits in the eastern midwood turned out to be a one-of-a-kind aberration - and life became an unending quest for something to eat.

Survival required a change in diet. Gradually, the aurumvorax digestive system adapted to handle metals other than gold, as well as gems and minerals. The aurumvorax learned to eat the iron ore found in the hillsides south of the Tangled Forest, and the onyx deposits hidden in the rosemary valleys north of Hap. Some suspect aurumvorax of devouring the secret jade caches of Myth Drannan royalty, hidden in subterranean vaults near the Standing Stone. The Cormanthor aurumvorax have also increased the proportion of red meat in their diets, favoring groundhogs, wild cats, and ferrets.

The changes in diet have also brought about changes in appearance and behavior. The Cormanthor aurumvorax have mottled coats, their golden fur streaked with dull reds and blues. While normal aurumvorax hides may fetch as much as 15,000-20,000 gold pieces, an elven woods aurumvorax hide might bring half that amount. When burned in a forge, a Cormanthor aurumvorax leaves behind about 50-75 pounds of gold. The claws are usually bright green or violet; collectors have paid up to 100 gold pieces per green claw, ten times that for the rarer violet claws.

To minimize the need for food, the Cormanthor aurumvorax hibernates for about three months, usually in the autumn and winter. A hibernating aurumvorax buries itself in mud or dirt, then curls into a ball with its head tucked beneath its legs.

Though an active aurumvorax breathes through its nostrils, a hibernating aurumvorax absorbs air through pores in its hide. A patch of skin about three inches in circumference remains exposed during hibernation. Unwary travelers may mistake this exposed skin for gold. The slightest disturbance - a touch, a loud sound - and a hibernating aurumvorax snaps to life, snarling and clawing at whoever had the misfortune to wake it up.

During the spring, many Cormanthor aurumvorax suffer from allergies. The allergies result in fits of sneezing, which merely annoy the aurumvorax, but may seriously inconvenience a traveler. An aurumvorax's spittle, expelled when the creature sneezes, can corrode metal, reducing a suit of armor to worthless rust in a matter of minutes.

Special Properties of the Cormanthor Aurumvorax

An aurumvorax hide may be worn as armor; the heavier the hide, the better the Armor Class. A 50-pound hide gives the wearer AC 3, a 40-pound hide provides AC 4, and a 30-pound hide furnishes AC 5. The wearer receives a +3 bonus on saving throws vs. normal fires and a +1 bonus on saving throws vs. magical fires.

Additionally, the hide grants nearly complete immunity to all nonmagical weapons made from a particular metal or mineral. For example, if the hide grants immunity to jade, the wearer suffers minimal damage (1 hit point) if attacked by a blade made of jade, a jade-tipped arrow, or a hurled chunk of jade.

The DM may randomly determine the metal or mineral by rolling on the following table, or he may select a particular substance. If he wishes, he may augment this list with other metals or minerals.

Metal/Mineral Immunity from Aurumvorax Hide

| d8 Roll | Metal/Mineral |

| 1 | Silver |

| 2 | Gold |

| 3 | Copper |

| 4 | Onyx |

| 5 | Jade |

| 6 | Turquoise |

| 7 | Opal |

| 8 | Azurite |

About 20 percent of Cormanthor aurumvorax suffer from allergies in the spring. During an encounter, an allergic aurumvorax has a 1 in 6 chance in any given round of sneezing instead of making a normal attack (sneezes are involuntary; the aurumvorax can't sneeze on purpose). The expulsion of spittle extends in a foot-wide spray about 10 feet long. The spittle has the same effect on metal as gray ooze (corroding chain mail in one round, plate mail in two, and magical armor in one round per each plus to Armor Class).

Bulettes

Everything about the Cormanthor bulette is awful - the way it eats (by swallowing live prey feet first, sometimes leaving the head), the way it sleeps (often napping in the middle of a meal, a victim squirming in its jaws), even the way it breathes (wheezing when it inhales, drooling when it exhales). Nothing is more awful than the way it mates.

At the end of summer, the male stakes out its territory in the starwood, ringing the boundary with corpses of deer and wild boar. The corpses usually attract predators, which the bulette destroys and adds to the ring. With the boundary complete, the bulette digs a shallow pit, then lines it with bones extracted from the corpses. For the next week or so, the bulette sits in the pit, chewing the bones and grinding them to a fine powder. It spreads the powder over the bottom of the pit, then tunnels underneath.

Within a month, a female bulette arrives, drawn by the odor. As she settles into the powder, the male bursts from the tunnel. They mate. The male wanders away. The female rests.

Gestation occurs in a matter of hours. By the following evening, the female has laid up to a dozen rock-hard, spine-covered eggs. By morning, the eggs hatch. While they're hatching, the female announces the event by bellowing like an elephant.

Once hatched, the young immediately attack the mother, attaching themselves to her feet, her tail, her snout. The mother responds by gobbling up as many of the infants as she can. The battle rages until the mother eats all the infants, or the infants kill the mother. Usually, the infants win, although it's rare that more than two or three survive. Those left alive celebrate their victory by devouring their dead siblings and whatever's left of their mother.

I told you it was awful.

Still, despite the obvious risks, should you hear the female bulette's distinctive birth roar, I suggest that you investigate. After it's been saturated with the fluid inside the eggs, the bone powder in the nest makes a potent fertilizer. A handful of powder applied to a seedling will result in a tree twice its normal height. The powder may have additional applications yet unknown; I suspect it may cause an apple tree to bear twice the normal amount of fruit, a rose to bloom in winter, and wheat to sprout in sand. Act quickly; the powder loses its special properties if it isn't removed from the nest within 48 hours after the eggs hatch.

Centaurs

You wouldn't know it now, but Cormanthor once teemed with centaurs. In the old days, if you rode a mile or two in any direction, chances were that you'd spot a centaur giving a lift to a hitchhiking halfling, or frolicking in a sunflower field with an elven child.

Not any more. A century ago, a plague swept through the midwood that caused several generations of centaurs to be born with their left hind feet three inches too short. The crippled colts could barely hobble, let alone run, making them easy pickings for dragons and other predators. Pleas for help went unanswered; the elves and halflings kept their distance, fearing they'd join the centaurs on the dragons' menu.

Within a few decades, the centaurs were all but wiped out. A population that had numbered in the thousands had been reduced to three tribes, each consisting of about a dozen families. Though eventually the plague played itself out and the dragons left for greener pastures, the legacy of death dramatically affected the behavior of the survivors.

Elsewhere in the world, centaurs tend to form self-contained communities, settling in glades and valleys which they seldom leave. The centaurs of Cormanthor, vowing never to repeat the mistakes of their ancestors, are constantly on the move. Staying in one place too long, they believe, invites trouble. The three tribes travel separately, each about a week behind the other.

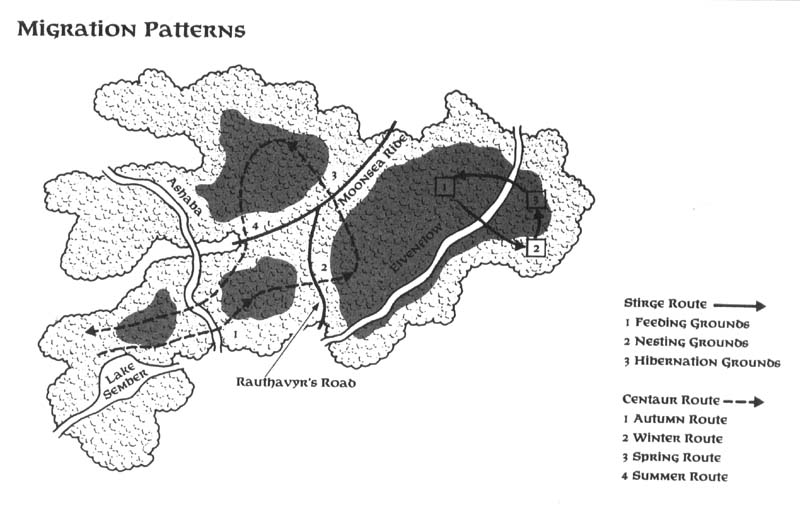

Migrating centaurs follow a more or less fixed route. In the summer, they settle in the midwood south of Semberholme, a relatively reclusive area that provides ample clover for grazing and cool water from Lake Sember for drinking and bathing. They journey east at the end of summer, stopping in central starwood pastures for the autumn, then continuing into the East starwood where they spend the winter. In early spring, they move to the West starwood, circle Myth Drannor, then return to the Semberholme midwood before summer begins.

The centaurs have carved out trails through the starwood that enable them to quickly traverse the dense forest vegetation. Any traveler following these trails can expect to cross the starwood at about twice his normal speed - providing, of course, he can find the trails in the first place. Hallucinatory terrain interrupts the trails at regular intervals, making them indistinguishable from the surrounding trees and brush. The centaur leaders create these illusions with magical amulets, gifts from a friendly human priest sympathetic to their plight. An observant traveler, however, may detect the illusions by looking for abnormalities. In some places, the illusory maples are free of birds. In others, the illusory bluegrass doesn't move when the wind blows.

Unlike their amiable ancestors, Cormanthor centaurs are anxious, distrustful, and hostile. They refuse to associate, let alone cooperate, with other sentient creatures. Strangers are greeted with volleys of arrows tipped with fungal poison; earthen mounds along their secret trails mark the graves of former trespassers. The tribes also maintain small flocks of falcons which they use as scouts and guards. Despite their foul attitudes, centaurs live in harmony with the environment, taking care not to overgraze a clover field or deplete a favorite catfish pond. They particularly enjoy pears and peaches, and will stray from their migratory routes if they catch the scent of an orchard. If you're thinking of luring a centaur with fresh fruit, don't bother. With a single sniff, he can usually tell if a peach has been contaminated by a human's touch, even if the human was gloved.

Chimerae

Two types of chimerae stalk Cormanthor: the mean ones, and the really mean ones. You can't tell one from the other, except for their lips. The mean ones have black lips, the really mean ones have red lips.

But I'm getting ahead of myself.

For a chimera of any lip color, life in Cormanthor is one long picnic. Everywhere it goes, it has something to eat. The goat head can munch crabgrass in the rimwood. The lion head can hunt antelopes in the midwood. The starwood provides a veritable banquet for the dragon head; it can begin with an appetizer of wild dog, have a warthog or two for a main course, then snack on a halfling for dessert.

While chimerae in other parts of the world tend to remain in territories of 20 square miles or less, the Cormanthor chimera is a true nomad. It wanders from place to place, seemingly at random, led by its stomach. A chimera who welcomes the spring with a wolf dinner in Semberholme might drift east for three or four days, scoop trout and dogfish from the Ashaba, then flap toward Ashabenford. After a hot meal - perhaps an elven explorer, fried crispy black with dragon breath - it may head to the central starwood, lured by the aroma of bear cubs. By late autumn, it could end up in Elven Court, where it might evict a badger family from a hollow oak trunk, eat the badgers, then move in for a snooze. It may slumber for as long as two or three weeks before its rumbling stomach awakens it for another cycle of snacks.

It's no surprise that the Cormanthor chimera is easy on the environment. It never stays still long enough to deplete a food source, leaving plenty for other predators. It has a generally positive effect on animal populations, preferring to eat weak and dying animals instead of strong and healthy ones. Like all scavengers, the chimera helps reduce disease and keep the forest tidy by consuming corpses, bones, and other debris.

Because the Cormanthor chimera favors no particular habit and is usually too lazy to maintain its own lair, it can pop up anywhere. It can pounce on a traveler from a tree limb or burst from a pile of fallen leaves. To cool itself in the summer, the chimera likes to bury itself in soft mud. That lump by the river bank might decide to have you for lunch.

Thankfully, the surplus of food in Cormanthor has dulled the chimera's hunting skills. As often as not, a chimera would rather wait for new prey than pursue a victim with a head start. It would rather withdraw than continue a difficult battle. If injured, it would rather look for a soft bed of ferns than search for the enemy who harmed it.

A hungry chimera can be an angry chimera. Like many of the monsters in Cormanthor, the chimera has had little contact with humans and doesn't know enough to fear their weapons or magic. The average chimera considers the average human about as threatening as a butterfly and much more filling.

A chimera prefers to attack by swooping from the sky with slashing claws and snapping jaws, but the dense vegetation discourages aerial assaults. Instead, the chimera hides in tall grass or behind a thick oak, then charges, leading with its lion head. Using its forepaw, it swats with the force of a war hammer. While the roaring dragon head keeps the victim's companions at bay, the lion head sinks its teeth in the victim's neck, snapping it with a single yank. A mature chimera attacks so smoothly and efficiently that its goat head may sleep through the entire procedure.

Fortunately, the chimera seldom cooperates with others of his species, so travelers will rarely have to face more than one at a time. Only during mating season, typically late in the spring, do chimerae get together. Females hate everything about the process and do their best to elude the males. Mating usually takes place in the rimwood, where there are fewer places for the females to hide. Good thing, too, since the female thrashes and spews fire during mating, and there isn't much in the rimwood to knock down or burn. Should the couple spot a potential meal - say, a curious adventuring party - they.ll interrupt their courtship, have dinner together, then resume their romance. The male will be just as eager as before, the female just as hysterically reluctant.

The female gives birth to as many as six young the following spring, depositing them wherever she happens to be at the time. A chimera makes a poor mother; though she produces black milk for several months, she nurses her brood for only a few days before abandoning them. She releases the excess milk while sleeping, often waking up in a pool of thick, dark liquid. Though most humanoids find chimera milk sour and undrinkable, orcs prize it as an intoxicant; a jug of chimera milk will often buy cooperation from an unfriendly orc party.

Now, about those red-lips...

All Cormanthor chimerae, regardless of lip color, like to fly to the top of the highest elms in the star- wood, settle down in the leaves, and bask in the sun. About 10 percent of these chimerae are born with light pink lips. Invariably, the pink lips become sunburned, an indignity not suffered by their black lipped cousins. The burned lips make eating extremely painful. Unable to enjoy their favorite pastime, the sunburned chimerae vent their frustration on any creature who gets in their way. They attack giant spiders, manticores, and even dragons, working themselves into a rage so out of control that their own well-being is no longer of consequence. A red-lipped chimera will not only fight to the death, it will pursue you the length of Cormanthor for the opportunity.

Dragons

Aside from the red dragon I saw high-tailing out of Myth Drannor, I've had few other firsthand experiences with dragons. While I haven't actively looked for them - a practice as risky as juggling wasp nests - neither have they found me. Either I'm too old to eat, or there aren't that many here in the first place. Since I'm sure a hungry dragon would be more than happy to have me for breakfast, I.ve concluded that dragons don't find Cormanthor all that hospitable. Why? Three reasons:

No Room: There's too many trees. A dragon couldn't fly 100 yards without colliding with an elm or bumping his head on a maple. While seemingly an ideal home for greens, the density of vegetation makes it difficult to get around. I suspect that the younger the green dragon, the more likely it is to lair in Cormanthor; by the time it reaches adulthood, it's probably ready for a roomier habitat.

No Food: A cousin of mine, who's made a study of such things, told me that a hundred years ago Cormanthor was crawling with green dragons. The dragons had a fondness for centaurs, who also occupied the forest in unprecedented numbers. The dragons feasted freely on the hapless centaurs and nearly drove them to extinction. The greens blamed each other for overharvesting their favorite food, culminating in an all-out war where they killed each other by the dozens, destroying a good chunk of the central starwood in the process. To this day, the aroma of chlorine breath still lingers. The acres of toppled hickory trees now serve as lairs for adders and wood beetles.

Today, the few remaining dragons find themselves in competition with chimerae and other large carnivores for the same food. A Cormanthor dragon may be forced to spend most of his time hunting; it takes a lot of hedgehogs and woodchucks to fill a dragon belly.

No Treasure: If dragons lusted for pine needles and daffodils instead of diamonds and gold pieces, Cormanthor would be a godsend. These woods lack the quantity of jewels and precious metals necessary to keep an avaricious dragon content, and with the exception of Myth Drannor, Cormanthor has few suitable cities to raid.

Of course, dragons do exist here, as they do virtually everywhere in the world. I discovered one quite by accident about a day's ride north of Myth Drannor.

On a gorgeous spring morning, I had climbed to the top of a birch-covered hill in search of catmint to season a stew. In the valley below, I saw a gold dragon roughly the size of a small castle, head in hand, listening intently to a pair of elves at his feet. The elves gestured wildly, pointing accusing fingers at one another; I was too far away to make out their words. An hour later, the dragon lifted his head into the air and roared loud enough to rattle the trees. The dragon snatched one of the elves, then soared away into the clouds, leaving the other elf gaping in astonishment. Elminster later told me that I had witnessed a trial adjudicated by His Resplendence Lareth, the King of Justice, ruler of the gold dragons.

The King had settled an elven dispute by carrying off the guilty party, probably to a prison in the Great Desert.

Undoubtedly, a few dragons still roam Cormanthor, but you're going to have to look hard to find them. A few observations, courtesy of my cousin, you might find useful:

- The green dragons of Cormanthor retain their love of centaur flesh. Unlike, say, red dragons, who devour centaurs whole, the greens find the tails distasteful. Should you see a tail that appears to have been ripped or nipped from a centaur's body, take it as a sign of a green in the area.

- Satyrs of the elven woods consider it good luck to spot a dragon in a rainstorm. Though I don't believe such a sighting actually affects one's fortune, this information may still come in handy. If you can convince a group of satyrs you've seen a rain-soaked dragon, they may more inclined to cooperate, hoping your "luck" will rub off on them.

- If a green dragon's eyes dart from side to side, it's in the mood for vegetation. If the eyes stare straight ahead, it's hankering for meat. Remember, though, that a hungry dragon will probably settle for whatever food happens to be available.

- If you think you saw a dragon, you probably did.

Fyreflies

Cormanthor must have the world's dumbest insects. To cool off, shrub beetles jump into the Ashaba, float until their spongy wings become engorged with water, then sink and drown. Seeking shade, horse crickets march into the open mouths of bluetail snakes where they're promptly swallowed.

Cormanthor fyreflies make shrub beetles look like geniuses. Most of the time, fyreflies are content to flit about the rimwood, gorging on cornflower pollen by day, flickering themselves silly by night. On clear summer evenings, however, fyreflies gather in frenzied swarms, rolling across the landscape and zig-zagging through the sky like uncontrollable fireballs. The swarms scorch everything in their paths, leaving behind broad swaths of smoking grass, blackened trees, and incinerated animals. The random devastation continues until the swarms dissipate from sheer exhaustion, or they scatter in the rays of the rising sun.

Have you ever seen an evening sky so rich with stars that it looks as if the gods had strewn the heavens with buckets of diamonds? It's just such a night that drives fyreflies out of their minds. They mistake the stars for rival flies trespassing on their territory. When attempts to drive off the stars with fiery displays and threatening motions invariably fail, the swarm's frustration turns to blind rage. The flies' reaction could be dismissed as humorous, even pathetic, were it not for the tragic consequences. Fyrefly swarms cause more fires than lightning, careless travelers, or any other forest creature; even chimerae and cockatrices have enough sense not to burn down their own habitats.

Two summers ago, a swarm ignited a pine forest in the rimwood south of Shadowdale, destroying the primary nesting ground of the needle wrens. As the needle wrens were primarily responsible for keeping the area's locust population in check, Shadowdale farmers now fear a locust plague; a swarm of locusts can chew up a corn field in a matter of hours. Nearly all the game fish in an Elvenflow tributary were killed following a fyrefly fire that burned down a beech grove; the fish that weren't poisoned by ashes died from the high temperatures. A rimwood fire east of Hap not only wiped out every last blade of peppergrass, it also seared the topsoil; autumn winds dried out and blew away the upper layers, spring rain washed away the rest. The area now consists of 40 square miles of dust.

Efforts to control the fyreflies have been futile. Rangers introduced giant wasps into fyrefly territory, hoping the wasps would eat the flies' favorite cornflower pollen and force them to move on. The fireflies learned to eat dried pigweed and quack grass instead. Fyreflies lay eggs in such massive quantities - I saw a wild pig suffocate when it fell into a hole filled with wriggling larvae and couldn't get out - that destroying their nests is a waste of time. I heard of an elven mage named Horquine who spent years trying to breed azmyths with a taste for fyreflies. Though each Horquine azmyth reportedly consumed triple its weight in fyreflies every day, the effect on the fyrefly population was incidental at best. Worse, the azmyths were unable to digest the flies' abdomens, the source of the magical flames. The azmyths expelled the organs as a blast of fire. Having never seen one, I can't say if these fire-blasting azmyth actually exist, but in the witch hazel groves of the eastern rimwood - a favorite azmyth roost - I've seen enough charred branches to make me wonder.

Gorgon

Heavy spring rains can cause the Ashaba and Elvenflow to rise, spill over their banks, and flood the surrounding areas. The shallow floods don't do much damage, however, aside from washing out some flower beds and a few ant colonies.

Within a week or so, the water recedes. Left behind are hundreds of fish and frogs, flopping helplessly in the mud. Some manage to find their way back to the water, but most die of exposure.

The aroma invariably attracts curious gorgons, who love the taste of fish but ordinarily have no access to them - gorgons swim like cows fly. The gorgons spend a few days stuffing themselves with grounded fish before depleting the supply. Most of the gorgons wander back into the woods, but a few remain on the shore, gazing longingly into the river. The lure becomes too great for some; they ease themselves into the water, gulping minnows and tadpoles, edging out a little farther, then farther yet, until finally they're in up to their noses. One slip on the muddy bottom, and it's all over; the gorgons plunge helplessly into the river and are swallowed by the currents. Unable to swim, they sink like bricks.

The benevolent Hexad have imbued Cormanthor gorgons with a safeguard. Within minutes after submerging, the gorgons turn to solid stone and enter a state of dormancy. The dormant gorgons settle on the bottom of the river where they can exist indefinitely, requiring neither air nor food.

Occasionally, powerful currents may wash a dormant gorgon ashore. If rain cleans away the grime and the sun warms its hide, the gorgon will revive, refreshed and as good as new, though perhaps a bit disoriented. More likely, however, a dormant gorgon will remain underwater until someone retrieves it. A diver may mistake it for a valuable statue. A fisherman may snag it, believing he's caught the world's heaviest bullhead. If cleaned up and allowed to dry out, a dormant gorgon will come roaring back to life, usually to the shock of its rescuers.

Owlbear

Like too many selfish, short-sighted species, the owlbears of Cormanthor ate up all the rabbits, serpents, and wolves in their starwood habitats as fast as they could. About a decade ago, it dawned on them that the days of unlimited food were gone. Faced with a dwindling population - and perhaps extinction - they'd either have to move on or wise up. Too stubborn to relocate and too pea-brained to get any smarter, the owlbears blundered into salvation by becoming insect farmers. On a routine hunt in the central starwood, an owlbear pack chanced across a pit containing a fallen oak tree, the rotten wood infested with giant harvester termites. The owlbears killed a few termites by smashing them with rocks, then fished them out with sticks. They found the termites reasonably tasty but not particularly filling. A month later, the owlbears returned to the pit. Now it was crawling with larvae. Thousands of termites had hatched since the owlbears' previous visit. The owlbears dumped in some rotting limbs and wet leaves, then sat at the edge of the pit, fascinated by the tiny insects chewing on the soft wood. Occasionally, the owlbears scooped up and swallowed handfuls of larvae. By the day's end, the owlbears had decided the larvae weren't half bad, and were certainly much easier to catch than wolves.

In the following weeks, the owlbears continued to dump rotten wood in the pit, and the termite colony continued to grow. The owlbears killed the soldier termites as soon as they hatched, since the solders had the annoying habit of spewing flammable liquid. The owlbears created more colonies by digging new pits and adding adult termites. The practice spread to other owlbear packs. Soon, owlbears throughout the starwood were subsisting on homegrown termites. The owlbear population stabilized, then slowly began to expand.

Owlbears eat adult termites by crushing them, eating the tender innards, then tossing the empty shells back in the pit. Owlbear saliva mixed with the decomposing termite shells has the fortuitous effect of attracting wild horses, who are irresistibly drawn to the aroma. Owlbears learned to hide behind trees near the termite pits, wait for a horse to investigate the odor, then dash from the trees and shove the horse into the pit. If the horse happened to be carrying a rider, so much the better. With a regular diet of termites, horses, and riders, the owlbears have never been more content - or better fed.

Interestingly, pyrolisks are also attracted to the termite pits and use them as nesting grounds. The owlbears despise the trespassing pyrolisks, but leave them alone - the owlbears would rather give up a pit than risk incineration. Once a pyrolisk hen finds a suitable pit - usually a smaller one, no more than 5 feet in diameter - she makes herself at home by eating all the adult termites, then scatters a few gems and other shiny objects around the rotten wood for decoration.

After laying one or two speckled eggs, the hen abandons the nest. The hatchlings subsist on the termite larvae until they're old enough to fend for themselves, a period lasting a few weeks.

Should the gems scattered among the wood tempt you into disturbing the nest, think again. Though hatchling pyrolisks can't attack - and the termite larvae pose no threat - panicky hatchlings can still cast pyrotechnics. The spell can ignite the larvae, causing the pit to spew flames and roast the hatchlings, the larvae, and anyone who happens to be standing around.

Termite Pit Fires

If ignited, a larval harvester termite pit spews a geyser of fire 10-20 feet high. The geyser burns for 2d4 rounds. Any creature in contact with the geyser suffers 4d4 points of damage; assume all termite larvae and pyrolisk hatchlings are incinerated. Any creature or character within 5 feet of the geyser suffers 1d4 points of damage.

Shambling Mounds

You wouldn't think the width of a blueberry stem could cause so much trouble, but it did. In the depths of the East starwood, a few miles north of Halfaxe Trail, grows a hundred acres of blueberry shrubs. Until they ripen, the berries are inedible, pale green and hard as stone. By late spring, the berries turn purple and swell to the size of watermelons. And the taste - imagine the sweetest blueberry you've ever eaten, glazed in honey with just a hint of cinnamon. Truly exquisite.

At one time, a small tribe of elves and dozens of shambling mounds subsisted on these berries. It was an unusual living arrangement, to say the least, since shambling mounds rarely congregate with others of their kind, let alone with other species. Thanks to the abundance and quality of the berries, the mounds and elves got along just fine. They ate at their leisure from summer through autumn, then stockpiled berries to get them through the winter. Spring brought a fresh crop.

One starless summer night, a couatl spiraled from the sky and crashed into the berry field. It died on impact, but not even the force of its landing could explain its strange markings and coloration. Both the mounds and the elves refused to examine the creature's remains any closer, convinced that they'd seen too much already. The superstitious elves were afraid of it, and the mounds, who might be tempted to eat it in other circumstances, were suspicious of its strange smell and stuck with the berries. In time, the corpse decomposed and was absorbed into the earth. The mysterious couatl was soon forgotten.

The following spring, the blueberries blossomed as usual. Days before the berries matured, their stems stretched and broke, and the unripened berries fell to the ground. The elves and mounds watched helplessly as one by one, the berries dropped, the thin stems unable to support their weight. Within a month, the entire crop was ruined.

The elves examined the bushes and discovered a brown dust covering the stems. The decomposing couatl had infected the field with a form of vine blight that had caused the stems to elongate. The elves blamed their leader for the crop loss, and at the urging of the leader's lieutenant, crushed his skull with a rock. The lieutenant, an evil priest who called himself Blackjackal, assumed leadership of the tribe. He convinced several of the shambling mounds to become allies. The elves and mounds now roam the starwood, assaulting innocents in the name of the dark god Talos.

The remaining mounds stayed behind, hoping the field would recover. Eventually it did, but not before the impatient mounds ate the old berries. The tainted berries caused the mounds' bodies to stretch until they resembled immense serpents, head and hands on one end, legs on the other. These serpentine shambling mounds still dwell in the area, nesting in mossy trees, guarding their blueberry field from trespassers.

Stirges

Stirges roost everywhere; where there's a blood supply, there's probably a stirge colony. Each colony follows its own migratory route, beginning in a forested area staked out by the adult feeders. A map elsewhere in this book shows the route of a typical colony. A colony's feeding grounds usually comprise a square mile of trees occupied by a sizable population of birds and mammals. By day, the stirges hang by their feet from the highest limbs in the area, sound asleep. By night, they suck blood from slumbering dogs, goats, and pheasants, avoiding bears and other large animals who might put up a fight.

Within a few months, the stirges will have begun to deplete the food supply. Prey becomes harder to find. Older, weaker stirges begin to die off. Fortunately, female stirges outnumber males, ten to one; by summer's end, half the females are ready to lay eggs. Stirges won't lay eggs in their feeding grounds, fearing competition from their own young. Early in the fall, the pregnant females migrate to a distant locale to deposit their eggs. Since they prefer barren fields, they often choose a site in the rimwood. Each female lays hundreds of eggs in a shallow hole, which she sloppily covers with a few inches of dirt and brush. The exhausted females then fly to a secluded forest for a few weeks of hibernation. Meanwhile, badgers and wild pigs are busy digging up the unprotected stirge eggs. All told, the stirges will lose about 90 percent of their eggs to predators.

By the beginning of spring, the dozing mothers awaken and fly back to their feeding grounds. In the interim, the bird and mammal population has revived somewhat, providing the returning females with fresh food. The food supply is almost always less than it was the year before. Sooner or later, the region will no longer be able to support the entire colony. Some stirges engage in cannibalism. A few relocate while others simply starve, too lazy or too dim-witted to move on. Meanwhile, the hatchling stirges, who emerge from their eggs in midsummer, migrate in a random direction. This frequently means flying 100 miles or more to establish their own feeding grounds. The cycle continues.

The broken shells of stirge eggs usually contain droplets of a greasy green jelly that developing stirges use for nourishment. Adult stirges find this jelly repulsive, possibly because they associate it with the demands of parenthood. A traveler can repel stirge attacks by smearing this jelly over his exposed flesh. The jelly from a dozen eggs will protect an average-sized human for an entire day. It smells bad, sort of a cross between pig's breath and rotten cabbage, but if you're truly interested in avoiding a nest full of stirges, you'll get used to it.

Treants

Treants thrive in Cormanthor, and not just because of the environment. Sure, the sun keeps them warm and well fed, and the frequent rains give them more than enough to drink, but if the treants hadn't established mutually beneficial relationships with other species, there might be a lot fewer of them. Like a normal tree, the treant depends on the health of its wood for survival. While the wood may appear to be as solid as stone, it's actually laced with tiny tubes. The tubes transmit food, manufactured in the leaves, throughout the treant's body. The tubes also carry water from the roots. If the tubes break down, the treant dies.

It's no wonder, then, that treants fear tube wilt more than any other disease. Caused by tiny spores in the soil, tube wilt enters the treant through the roots. Once inside the trunk, the spores multiply rapidly and become fungal growths that feed on the heartwood, the core of the trunk that contains most of the food tubes. The treant literally rots from the inside out. Within a few months, the treant collapses, its trunk too weak to support the weight of its limbs. It dies an agonizing death shortly thereafter.

Cormanthor treants have successfully combatted tube wilt by serving as hosts to a special species of rot grub with a voracious appetite for rotten wood. A treant suffering from a tube wilt infection opens a small crack near the base of its trunk, then stuffs the crack with decaying bark. Rot grubs, attracted by the bark, enter the crack and worm their way inside the treant.

The grubs burrow through the trunk, eating both the rotten wood and the fungi. Thereafter, the grubs remain inside the treant, keeping the treant free of decay and preventing a recurrence of tube wilt. The grub burrows don't harm the treant; in fact, they seem to enhance the flow of water and nutrients. Older treants may house hundreds of grubs. A woodsman attempting to chop down a treant may be greeted with a shower of grubs when his ax splits the bark.

Bark-eating creatures, such as woodchucks and certain types of wild horses, also pose a threat to treants. To scare off predators, many treants surround the bases of their trunks with a special species of violet fungus. Unlike normal violet fungi, which are 4-7 feet tall and almost exclusively subterranean, Cormanthor violet fungi rarely exceed 3 feet in height and grow on the forest floor. Tiny tendrils extend from the base of the fungi, tap into the treant's roots, and worm upward into the treant's trunk. The fungus lives on the treant's sap.

Should a predator threaten the treant, the fungus flails with its branches, attempting to rot the predator's flesh. A treant may be surrounded by as many as six violet fungi, but two or three are typical. When the treant moves, its fungi move with it.

Treants also risk damage from bark beetles, which burrow under the bark to lay eggs, and leaf ants, which chew holes in the leaves. To deal with these pests, treants encourage azmyths and large bats to nest in their limbs. The azmyths and bats enjoy the privacy of the treant's leafy crown, and feast on banquets of fat beetles and crunchy ants.

Black squirrels also make their homes in the treant's thick foliage. The squirrels enjoy nibbling on the female treant's off-shoot stalks. The stalks that survive the nibbling eventually become new treants. Since Cormanthor treants almost always generate more stalks than the forest can support, the squirrels help limit the population.

So what are the chances of finding a treant with all of these creatures? It depends on where you look. The birch treants of the rimwood - identifiable by their smooth white bark - usually have rot grubs in the trunk, purple fungi around the base, and azmyths and black squirrels in the branches. These treants grow exceptionally long roots to get to the deep water table, anchoring them in place for periods as long as six months; they need all the help they can get to survive.

The sap of the birch treants has a delectable aroma, a combination of lemon and mint. It can be used to make perfumes and food flavoring. Most midwood treants resemble golden willow and black locust trees. Webs of deep grooves cover the bark. The midwood treants share the attitude of treants elsewhere in the world: generally passive, but quick to confront evil. Many have violet fungi guardians, necessary to protect them from brush rats bent on digging nests under their trunks. Black squirrel tenants are also common. Midwood treant bark can be boiled to produce gold and black dyes.

Starwood treants look like dark brown oaks and mist gray elms. All have diamond-shaped patterns etched into their bark. About half share the midwood treants. docile personality and hatred of evil. The other half tend to be hostile; the starwood contain so many potential enemies that the treants prefer to strike first and negotiate later. A starwood treant may contain any combination of rot grubs, violet fungi, azmyths, and black squirrels. The leaves, when eaten, will cure certain fever plagues.

Cormanthor violet fungus flails with 1-2 tentacles, each 1 foot long. Except for the smaller size, it resembles a normal violet fungus in all other respects.

Water Nagas

The water naga undergoes a rigorous - some would say gruesome - series of transformations from egg to adult. To the unwary, each state poses a threat.

Adult water naga spend the winter hibernating in deep holes dug in the floors of ponds or rivers. They emerge in early spring and, after eating a hearty meal of frogs and fish, mate underwater. The female lays 100-500 eggs in the deepest area of the pond, then covers them with mud. The mud conceals the eggs and keeps them warm.

Water naga eggs resemble dark green spheres, about 3 inches in diameter, coated with a protective layer of clear jelly. The jelly provides nutrients for the developing naga and also deters predators. If touched, the coating attaches to the predator's flesh.

In a matter of minutes, the predator's body transforms into naga egg jelly. Despite this unique defense, rarely do more than half of the eggs hatch; about 30 percent are infertile, another 20 percent fall victim to low temperatures and various diseases. If you fish an egg from the water - use a staff or a metal pole - the coating will dry out and become inert in about an hour. The dried coating can be used as an antidote for crystal ooze poison. By mid-spring, the naga eggs begin to hatch. A typical hatchling looks like a footlong black worm with a pointed head and a circle of spikes around its neck. It breathes water with four pair of gills under its chin.

Hatchlings spend the daylight hours resting on the floor of the pond, then rise at night to feed on minnows and decayed plants. When a predator approaches, the hatchling becomes as rigid as stone. The rigid hatchling thrusts itself at the predator like a tiny spear, its neck spines erect. If the predator survives the attack, the hatchling can withdraw and try again. Perhaps a fourth of the hatchling naga survive this stage; the rest are consumed by giant carp and other carnivorous fish.

If you catch a hatchling - they occasionally attach to fishing lines - strip off the neck spikes with a sharp blade. A handful of spikes, when ground to powder and consumed, gives you the effect of a true seeing spell, enabling you to see all things as they actually are.

The hatchlings grow quickly, reaching a length of 10 feet in a matter of weeks. During this time, their neck spikes fall out, and they begin to acquire their characteristic scales (emerald green in reticulated patterns with pale jade green) and red spikes along the length of their spine. They also grow lizardlike legs, a pair at each end. Lungs develop, enabling the adolescent naga to crawl ashore and breathe air. Though it can still breathe water, the naga spends most of its adolescence on land, creeping through the grass for rats and slithering up trees for bluebirds.

All but the most ferocious predators, such as chimerae and dragons, avoid the adolescent naga. If the naga can't frighten them away, it can usually outrun them; the naga's legs allow it to move as fast as a jackal. The intact hide of an adolescent naga, including the leg skin, can bring as much as 5,000 gold pieces from collectors.

By late summer the adolescent has grown to its full 20-foot length. At this time, the naga enters its final stage by shedding its outer layer of skin. It scrapes against rocks or other sharp projections until the skin peels off in a single piece. Its head comes off as well, along with its legs. A tiny bud resembling a miniature human skull appears where the serpent head used to be. Over the next few days, the skull expands and becomes covered with scaly flesh. The water naga is now mature. The shed skin, complete with serpent head and legs, can fetch 35,000 gold pieces or more.

The mature water naga can breathe both water and air. It kills prey, usually mammals such as wolves and wild dogs, with its poison bite or constrictive coils. It often lures victims with magically created traps. The water naga of the Elvenflow lurk in shallow tributaries obscured with wall of fog. Those living near the Ashaba hide in elm trees, ensnare victims with web, then drop from the branches. I've heard of water naga mating with couatl north of Myth Drannor, their offspring having the abilities of both parents, but as far as I know, it's only a rumor.

- Elven Forest Water Naga Egg

- Elven Forest Water Naga Hatchling

- Elven Forest Water Naga Adolescent

- Elven Forest Water Naga

Worgs

The worg occupies an enviable position in the food chain. It's large and strong enough to bring down wild boars, yet small and quick enough to elude chimerae and other predators. No wonder the worg thrives here, particularly in the North starwood where they're as thick as rabbits.

Though the starwood provide a comfortable habitat for the worg, with plenty of game and more than enough brush for lairs, it also poses a problem. Every autumn the oaks cover the forest floor with a carpet of leaves as high as the worg's neck. Not only do the leaves hamper the worg's movement, they also make it difficult for the worg to stalk prey. An alert deer can hear a worg crunching through brittle leaves a hundred yards away.

The worg has solved this dilemma with a clever adaptation, the result of a gift from the Hexad, the effect of residual magic from Myth Drannor, or perhaps a combination of both. Worgs of Cormanthor have developed the ability to walk on top of fallen leaves, hovering a fraction of an inch above the surface.

Additionally, they can walk on fresh snow without sinking, run through a muddy field without leaving tracks, even dash across the surface of a pond without getting their feet wet. Worgs can use this ability at will; a worg can swim or bury itself in leaves whenever it likes.

Worgs occasionally allow goblins to use them as mounts. However, Cormanthor worgs are notoriously cranky. Should a goblin make excessive demands of a worg - such as ordering it to leave the comfort of the starwood - it is as likely to devour its rider as comply.

Worg Surprise Bonus

When a Cormanthor worg moves across the top of fallen leaves, fresh snow, water, or similar surfaces, its opponents suffer a -4 penalty to their surprise rolls.